- Madonna in the “Vogue” music video

Voguing: Madonna and Cyclical Reappropriation

by Stephen Ursprung, Smith College

Introduction

Voguing has left its mark on the world largely due to the commercial success of the Madonna song of the same name. On the surface, voguing appears to be the dance of black gay men that has been appropriated by popular culture. However a close examination of the form reveals that voguing gives a voice to the oppressed: the gay, lesbian, transgendered, bisexual, black, latino, female, and otherwise marginalized subcultures of American society. Although characteristically American in its geographic roots, Voguing has evolved in a community that pays homage to global culture and celebrity. Furthermore, voguing continues to hold relevancy thanks to an ongoing reciprocating exchange of influences with commercial entertainment.

Origins of Voguing: Holding Court in the Ballroom

Voguing first found its roots in Harlem, the neighborhood of Manhattan directly north of Central Park. Characteristically black and latino, Harlem has historically been home to marginalized communities. Where there is oppression and poverty, there is always art and creativity, and Harlem is certainly no exception. For the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Transexual (LGTB) communities in Harlem, creativity found its home in the ballroom culture. Ballroom culture saw people group together in social circles, called houses. These houses act like families; in a society filled with individuals cast out of their homes for being perceived as moral abominations and living a life of taboo, the house system provided a support system to those in need and trained young newcomers how to compete in the ballroom.

Similar to beauty pageants, balls test the creative and artistic talents of the contestants in their ability to impress the crowds as well as judges. Men compete to pass as straight men, biological women, and everything in between. Women compete to pass as straight women, biological men, and anything else. There are a plethora of subcategories: “realness,” “executive,” “military,” etc. Regardless of the competition, categories provide an escape from the pain of oppression felt by these individuals in a heteronormative world. I would argue further that the ballroom culture was not only born out of a need to respond to racism and heteronormativity, it was a response to heterofascism, gendernormativity, conformativity, and the socioeconomic oppression enforced by classism.

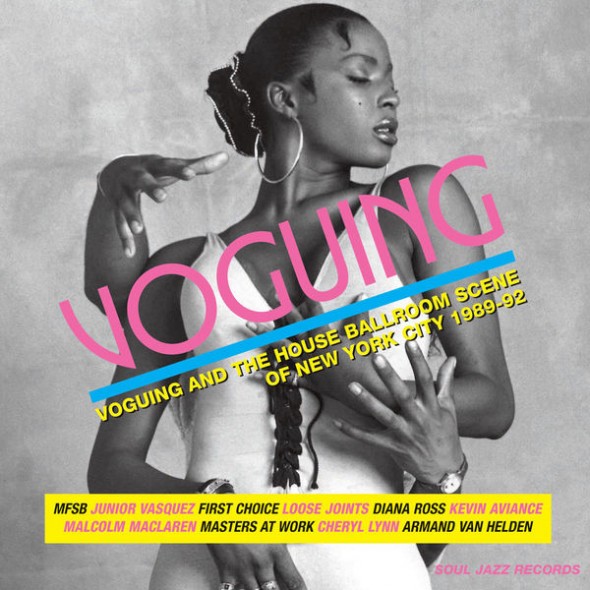

An album cover advertising music from ballrooms.

The movement itself is unique and easily identifiable. With sharp, angular gestures of the hands, vogue dancers frame their face and bodies as if performing for a fashion photographer. The evolution of the movement itself is eloquently described by the late Willi Ninja, mother of the House of Ninja and one of the most prolific and globally known vogue dancers and choreographers. In this clip, from Jennie Livingston’s critically acclaimed documentary Paris Is Burning, Ninja describes the subversive power of voguing:

[dailymotion]http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1vdtt_paris-is-burning-the-origins-of-vog_shortfilms[/dailymotion]

As described by Ninja, voguing is essentially a form of battling. Like bboying and breakdancing, voguing provides a safe and creative alternative to outcasts in Harlem. These dancers compete and earn respect and notoriety without resorting to violence or crime. Regardless of how these dancers “read” each other or “throw shade,” there is an underlying assumption of mutual respect and compassion. Even though each house competes to earn the most titles at each ball, the community benefit of the ballroom is continually respected and cherished by all those that participate.

Not only does this construct a nurturing and supportive environment to the participants, the formation of ballroom culture guaranteed longevity and immediately challenged young dancers to master the moves and techniques of their teachers in addition to coming to each competition with new and innovative moves and tricks to give them competitive advantage.

Global Roots

Even in name, voguing finds its roots in global popular culture. It is named after the popular magazine Vogue, which is a powerhouse in fashion journalism that is published in 8 different countries and follows fashion trends all over the world. By emulating the preening and detail of fashion posing and modeling, voguing establishes global relevancy by referencing universally recognized gestures and stances.

The obsession with celebrity also deepen voguing’s roots in global culture. Participants in drag balls mimic the fashion of global celebrities as a way to live out fantasies of grandeur without the reality of wealth. By perpetuating a referential homage to global culture, vogueing is a unique example of American vernacular movement based in global trends rather than U.S.-centric experiences.

Madonna: The Catapult into the Public Eye

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuJQSAiODqI[/youtube]

Voguing was first appropriated by pop culture by pop music icon Madonna in her 1990 single “Vogue.” In Patricia Hluchy’s review of Paris Is Burning she writes,

Combining gymnastic contortions with the preening moves of fashion models, it is a highly vampish style—which perhaps explains its appeal for Madonna, pop music’s reigning siren. In a recent interview with the Los Angeles gay-culture magazine The Advocate, the singer said she discovered voguing while planning last year’s [1990] Blond Ambition tour. At a New York City disco, she encountered some gay men who regularly attended the so-called drag balls where voguing was invented, and she said that she was “blown away.” Madonna went on to write her song about the dance, and recruited some of the drag-ball stars to perform on her tour. (Hluchy)

The drag-ball stars Hluchy refers to were members of the house of Xtravaganza. As chronicled in the Madonna documentary Truth or Dare and the recent voguing documentary How Do I Look? (visit the website for more information), Jose and Luis Xtravaganza designed and choreographed the dance sequences for the music video. The video also served to reference the glamor and elegance of celebrities ranging from early Hollywood stars through the contemporary artists of 1990. Ever since Madonna imprinted voguing into the minds of pop music consumers worldwide, the dance form has enjoyed a continual exchange with popular culture. While in its early days voguing appropriated the fantasy of fame, the fame of voguing fueled mutual dependency and inspiration between mainstream commercial entertainers and the participants of the underground drag ball scene.

By bringing voguing into the limelight, Madonna created a market for voguing in the commercial entertainment world. As interest in voguing spread, the popularity of the already critically-acclaimed Paris Is Burning skyrocketed. Other dancers outside of the the house of Xtravaganza also highlighted in the film catapulted to fame. One of those dancers, Willi Ninja, whom I have previously mentioned, became one of the most recognizable vogue dancers, choreographers, and modeling coaches in the world.

Vogue legends Luna Khan, WIlli Ninja, and Jose Xtravaganza

In her obituary article after Ninja’s death in 2006, New York Times columnist Lola Ogunnaike remembers Ninja:

An androgynous, self-described “butch queen,” Willi Ninja taught vogueing [sic] throughout Europe and Japan, modeled in runway shows for the fashion designers Jean Paul Gaultier and Thierry Mugler and danced in music vides. He also taught models how to strut, giving stars like Naomi Campbell pointers early in their careers. Most recently, he worked with the socialite Paris Hilton, whose red carpet sashay has since become her signature. In 2004, he opened a modeling agency , EON (Elements of Ninja), but he never gave up dancing, appearing on televisions [sic] series like “America’s Next Top Model” and “Jimmy Kimmel Live,” and dropping in at local clubs. (Ogunnaike)

Ninja’s success is indicative of the type of apetite popular culture had for voguing. In my own experiences, I have seen a continually increasing number of voguing classes taught in commercial dance studios all over the country. At the popularly known Broadway Dance Studio in New York and Millenium Dance Complex in Los Angeles, students can study not only with vogue instructors from the early ballroom days, they can learn from instructors that mastered voguing in ballrooms in London, Toronto, Chicago, and countless other cities previously unconsidered in voguing’s history. Not only does voguing reference a global culture, it has become a global network and a commercial phenomenon of global culture.

After Madonna: Shift in Ballroom Culture

As the global obsession with voguing fell out of the limelight, the focus of the ballroom scene shifted. While still emphasizing community-based support and striving for innovative new dance steps, ball culture has devoted itself to rebuilding the community in the wake of AIDS. As chronicled in Paris Is Burning, many participants in ball culture make their livings in the sex industry and risk infection and violence. Even now, decades after the hight of the AIDS crisis, voguing legends continue to succumb to the disease. Most recently, Willi Ninja passed away at the age of 45 after a long battle with AIDS-related heart failure. By forging a long-standing relationship with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and various HIV/AIDS organizations, ballrooms have focused on providing sexual health and lifestyle education to newcomers too young to have experienced the outbreak of AIDS and the immediate loss of a generation of gay men. How Do I Look? documents this shift towards health education.

(Another) Reinvention of Madonna

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYkwziTrv5o[/youtube]

On March 21, 2012, Madonna caused a stir when she released her music video for her newest single “Girl Gone Wild.” The song references her continuing experiences as a lapsing Catholic and sexual deviant. The video depicts Madonna as the only woman in a sea of scantily clad (presumably) gay men—mostly famous male models. Most fans and critics have marked “Girl Gone Wild” as a return to “Vogue.” Like “Vogue,” the video is black and white and references Madonna’s Blond Ambition years in countless ways.

The most striking reference to the “Vogue” video is the dancing. Most importantly, Madonna enlisted the Ukrainian boy band Kazaky to choreograph and perform in the video. Kazaky has become a viral phenomenon on YouTube due to their intricate choreography, subversive play on gender performativity in fashion and popular media, and their wardrobe (most notably their signature 5.5 inch stilettos).

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n7-T8FSUQ_w&feature=plcp[/youtube]

Madanna perpetuates the codependence of celebrity and voguing yet again by refocusing our attention on the brilliantly referential movement form. This time around, however, she does even less to mask the sexually exploratory and indulgent influence on voguing—the intrinsically sexual and exploitative nature of voguing is certainly performative, however it is this exaggeration of sexuality that makes the movement somehow more honest and human.

In MTV’s review of the video, they note,

“Those moves! Those angular, cutting arm, leg and body movements. Check. A bunch of scantily clad male dancers posing in formation. Check… Madonna and her dancers are definitely “vogueing”—or at least as close to it as she’s gotten since she struck her pose most famous post in 1990… She embraces the connection [to the gay community in “Vogue”] and appears to be doing the same here. In “Girl Gone Wild,” we have two male models gnawing at the same apple, dancers in heels (and little else) and many, many suggestive close-ups celebrating the male form. (Mitchell)

Conclusion

Voguing continues to forge a path of global relevancy through it’s unending reference to global culture, celebrity, and fashion. Through a close connection with the continued commercial success of Madonna, a woman known for constant reinvention and commercial reincarnation, voguing has solidified itself as an unapologetically staple of global society.

Selected Bibliography

Bleyer, Jennifer. “Life’s A Mini-Ball.” The New York Times. 29 June 2008: CY6. Print.

Freeman, Santiago. “Strike a Pose 2.0.” Dance Spirit. Jul/Aug 2008 Vol. 12 Issue 6: pgs 112-115. Print.

Hlutchy, Patricia. “The World of Voguing.” Maclean’s. 13 May 1991: pg. 49. Print.

Holden, Stephen. “In the Margins of 2 Minorities: A Double Fringe.” The New York Times. 23 July 1993: C3. Print.

How Do I Look? dir. Wolfgang Busch. Web. 5 April 2012. <www.amazon.com>

Mitchell, John. “Madonna’s ‘Girl Gone Wild’ Video: Five Key Nods To Her Past.” MTV Reviews. MTV, INC. 21 March 2012. Web. 25 March 2012. <http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1681501/madonna-girl-gone-wild.jhtml>.

Ogunnaike, Lola. “Willi Ninja, 45, Self-Created Star Who Made Vogueing Into an Art.” The New York Times. 6 September 2006: D8. Print.

Paris Is Burning. Dir. Jennie Livingston. Web. 1 March 2012. <www.netflix.com>.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.