Transcript:

September 22, 1962

Dear Dr. Beuscher,

Your letter came today, at a most needed moment, and I feel the way I used to after our talks—cleared, altered and renewed. I am really asking your help as a woman, the wisest woman emotionally and intellectually, that I know. You are not my mother, but you have been the midwife to my spirit. There are breaking points and growing points; I had my last great bout ten years ago when I met you, and now that I am in the middle of another, in soul-labor and soul-pain as it were, I turn to you again, because you are the one person I know who will not advise me to numb or degrade or give up or diminish myself. If I could write you once a week for the next few weeks, & get a short answer, practical, a paragraph—your paragraphs are worth a ton of TNT—it would be the greatest and best thing in my life just now. My life at present is made up of amiable bank managers accountants, insurance salesmen, solicitors and the local doctor. The midwife is sensible and kind but totally without imagination or much intelligence. I value my life, what it can be in all its yet unworked veins of creativity and variety, so much that I would spend my savings in America to come over by jet on the chance of having an hour a day for a week talking to you, but if you were able to manage a paragraph or so, I think this would not be necessary. I want to be able to initiate my new life, my separate life, as soon as possible, and for this a live-in nanny is essential, and I had probably better save what I’ve got left for this. We lived off my $2,000 nanny-grant-to-write-a-novel all this year: as soon as the last payment stopped, Ted “got courage” and left me. So, no 2nd novel, yet, no nanny, no money. And no Ted.

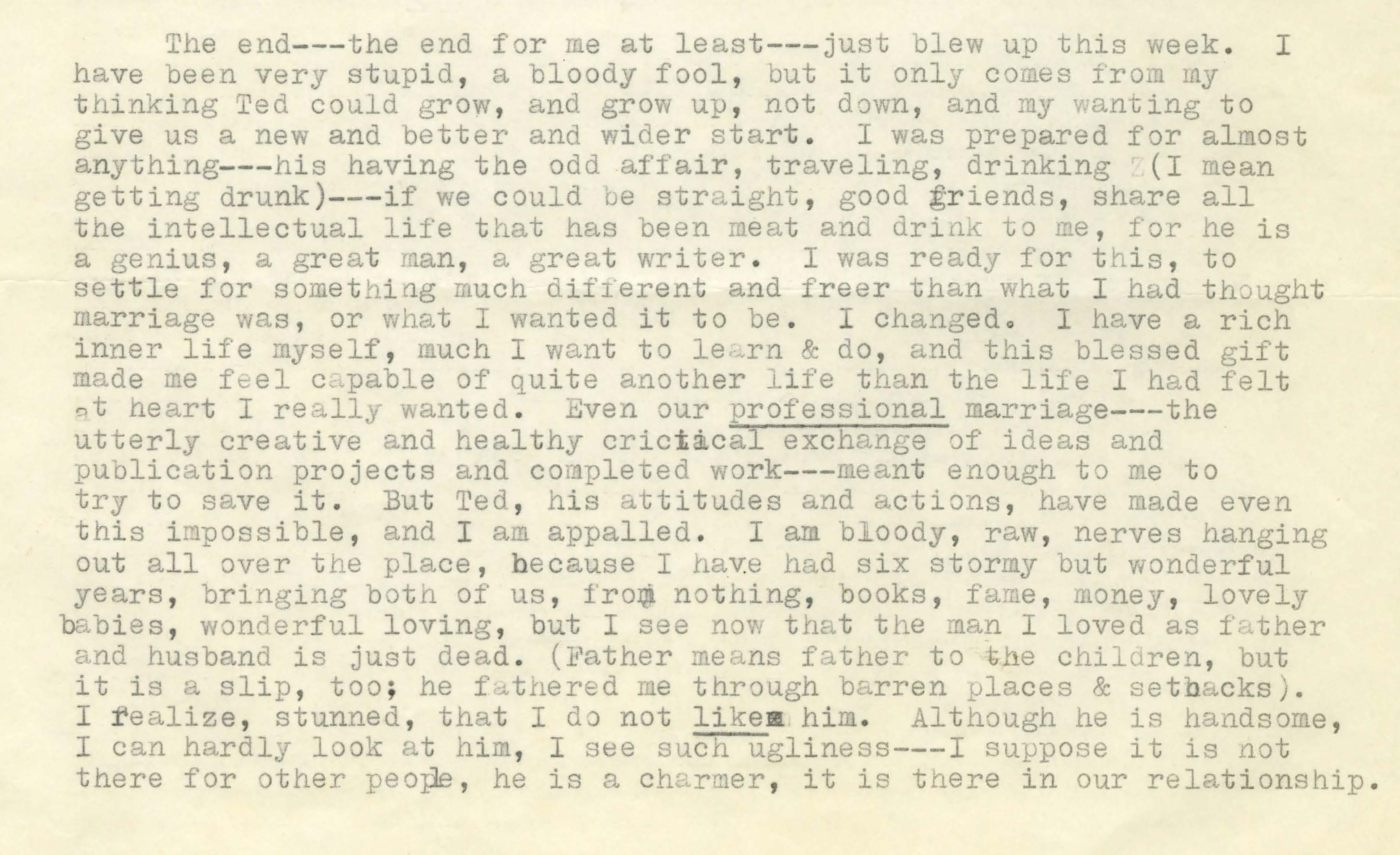

The end—the end for me at least—just blew up this week. I have been very stupid, a bloody fool, but it only comes from my thinking Ted could grow, and grow up, not down, and my wanting to give us a new and better and wider start. I was prepared for almost anything—his having the odd affair, traveling, drinking (I mean getting drunk)—if we could be straight, good friends, share all the intellectual life that has been meat and drink to me, for he is a genius, a great man, a great writer. I was ready for this, to settle for something much different and freer than what I had thought marriage was, or what I wanted it to be. I changed. I have a rich inner life myself, much I want to learn & do, and this blessed gift made me feel capable of quite another life than the life I had felt at heart I really wanted. Even our professional marriage—the utterly creative and healthy critical exchange of ideas and publication projects and completed work—meant enough to me to try to save it. But Ted, his attitudes and actions, have made even this impossible, and I am appalled. I am bloody, raw, nerves hanging out all over the place, because I have had six stormy but wonderful years, bringing both of us, from nothing, books, fame, money, lovely babies, wonderful loving, but I see now that the man I loved as father and husband is just dead. (Father means father to the children, but it is a slip, too; he fathered me through barren places & setbacks). I realize, stunned, that I do not like him. Although he is handsome, I can hardly look at him, I see such ugliness—I suppose it is not there for other people, he is a charmer, it is there in our relationship.

After the first blowup, when mother was here—and I think Ted secretly meant her to be here; when he wants to torment me, knowing my horror and fear of her life & the role she lived as a woman, he tells me I am going to be just like her—Ted came home and said it didn’t work, the affair was kaput. I believed this. He said he would be straight, now that I wouldn’t be tearful or try to stop him from anything—he only wanted to go up to London on drinking bouts with a few friends. He went up half the week every week. The minute he came home he would lay into me with fury—I looked tired, tense, cross, couldn’t he even have a drink, what sort of a wife had he married etc. I was dumbfounded—his fury seemed all out of proportion with what he said he’d been doing, & I was quite happy, if understandably apprehensive, getting on at home. Then I found out by accident that this little story & that about what he’d been doing weren’t true. Mrs. Prouty treated us to a night & a day at the fanciest hotel in London & I never had such good loving, felt it was the consecration of our new life. He went to have a bath & I next saw him coming in fully dressed with funny pleased smile. He had called some friends to have a drink. Fine, said I, I’d love a drink. No, I was to go home on the next train. He didn’t come back for a couple of days and even then I thought he was doing what he said, I was trying so hard to believe he knew what straightness and reality meant to me. Now, of course, I see this saying the affair was over was just an elaborate hoax, & his furies equal to what he was really doing.

I had the flu, as I said, was terribly weakened by this & lost of a lot of weight suddenly. We had an invitation to go to Ireland to a poet’s house in the wilds of Connemara (I’d just given him a £75 poetry prize, so this was gratitude) & sail on the old Galway hookers he’d salvaged & ran in summer as fancy tourist fishing yachts. I got a flossy nanny for the babies. All I wanted was my health back—I had been on a liquid diet for weeks. Well it was wonderful in this way—an Irish woman cooked, got me to eat 2 eggs & half a loaf of her brown bread & her cows’ milk & hand churned butter for breakfast, the sea gave me my appetite back, and I love fishing. Ted lasted four days. He left while I was in bed one morning saying he was going grouse shooting with a friend. I haven’t seen him since. He left me with all the baggage to carry back, and I got a telegram when I got home, addressed from London, to keep the nanny, he might be back in a week or two. I had let the nanny go by the time I got the telegram & made him dinner, & she had another job when I called her. Then I had all the fun of reading the real meaning into what I found so emotionally upsetting week after week after week. Ted is very faithful. He stopped sleeping with me. He kept groaning this other woman’s name in the night. I see now it is she he was being faithful to, but I was in agony, not know what was wrong. He did tell me that when we were courting the women with whom he boarded crawled over him all night but he refused them: I thought this was only a historical statement, but now I see this is how he is ^[+ why he has stopped sleeping with me.] And the one or two times he did turn to me it was degrading, like going to the toilet, he made so sure I felt nothing, and was tossed aside after like a piece of dog sausage. Well I am neither my mother nor a masochist; I would sooner be a nun than this kind of fouled scratch rug. Ted is so stupid. He honestly is sure I would rather have this than nothing. He doesn’t see how I can get on without him.

I have got someone to take care of the children and am going to London this Tuesday to see a very kind-sounding solicitor recommended to me by my accountant in order to get a legal separation . Ted seems to need to come home every week to make my life miserable, kick me about & assure himself that he has a ghastly limiting wife, just like his friends do, three of whom have left their wives this year. He hates Nicholas. When I had the flu I told him to be sure Nick was strapped in his pram as otherwise he would fall out, was he strapped? Yes, Ted said. Later I heard a terrible scream. The baby had fallen out onto the concrete floor, Ted had never strapped him in, and did not even go to pick him up, the cleaning lady did that. He was unhurt. See, said Ted. He could have had concussion or broken his spine. He has never touched him since he was born, says he is ugly and a usurper. He is a handsome vigorous child. Ted beat me up physically a couple of days before my miscarriage: the baby I lost was due to be born on his birthday. I thought this an aberration, & felt I had given him some cause, I had torn some of his papers in half, so they could be taped together, not lost, in a fury that he made me a couple of hours late to work at one of the several jobs I’ve had to eke out our income when things got tight—he was to mind Frieda. But now I feel the role of father terrifies him. He tells me now it was weakness that made him unable to tell me he did not want children, and that his joyous planning with me of the names of our next two was out of cowardice as well. Well bloody hell, I’ve got twenty years to take the responsibility of this cowardice. I love the children, but they do make my plans for a life on my own quite difficult, now they are so small & need such tending. He has never bought them clothes, my mother has sent these, but now I hear she has lost her job, the department is closed, so he’ll just have to pay up.

Money is a great problem. We were doing fine, the house paid up, a car, starting to save a bit—now he is spending over $100 a week of our joint savings on his London life. He has never paid a bill—always misads & louses up the checkbook at the times I’ve asked him to take that over, so I’ll have to make it right—and has no idea of yearly rates, taxes, bills. I have the financial year always pretty well in hand, & know when to say we should work hard. He means well—says all he wants is to live his own life & send us 2/3 of what he earns. But unfortunately the kind of women he chooses do not mean well. I even think someday he might try to take Frieda from me. She flatters his vanity. “Kiss daddy”, he says when he comes home, making no move toward her. That is as far as fatherhood goes; she is very wild & lively and pretty. The woman I guess he’s now living with spent all her time here taking pictures of Frieda & buying her presents. I trust noone now. I dearly love Ted’s mother & father & aunt & cousin & uncle—but God help me when Olwyn takes over. Ted has even told the doctor I thought I had “canine influenza.” to “show I was unstable”; this was a joke on my part; our guests were called the Kanes & I got the germ from them. But I am upset about this—I honestly think they might try to make my life such a hell. I would turn over Frieda as a sort of hostage to my sanity. I am so bloody sane. I am not disaster-proof after my years with you, but I am proof against all those deadly defences—retreat, freezing, madness, despair—that a fearful soul puts up when refusing to face pain & come through it. I am not mad; just fighting mad.

One good thing about Ireland, I found a fine woman, one of the old horse-and-whiskey-neat set, with a gorgeous cottage & views she would let me for the winter. She has a Connemara pony, her own TT tested cows (which I’d like to learn to milk) & butter churn & could show me all the wild walks & would welcome the children. I got on there so well, I think I will rent Court Green, if I can, for the three worst winter months & go to Ireland, coming back in spring with the daffodils & kinder weather. The children would love this, I would be safe from Ted, & get the first months of separation underway in a fresh setting. I can’t stand the feeling here now of my being left, passive. I need to act. To leave the place myself. When I come back it would be to something else, and I would have had time to fatten and blow myself clear with sea winds & wild walks. This is where my present instinct to salvation leads.

The worst thing is, as you say, psychologically, the fear and danger of being like my mother. Even while she was here she began it: “Now you see how it is, why I never married again, self-sacrifice is the thing for your two little darlings etc. etc.” till it made me puke. From the outside, our situation is disconcertingly similar—two women “left” by their men with two small children, a boy & a girl & no money. Inside, I feel, it is very different. I want it to be. Mother has suggested I live with her, as she lived with her mother. I never could or would, & right now I never want to see her again. She was always a child while my grandmother was alive—cooked for, fed, her babies minded while she had a job. I hated this. Her notion of self-sacrifice is deadly—the lethal deluge of frustrated love which will lay down its life if it can live through the loved one, on the loved one, like a hideous parasite. Lucky for me, I love my writing, love horse-riding, which I’m learning, love bee-keeping and in general can expand the area of my real interests so that I think my children will have a whole mother who indeed loves them, with vigor and warmth, but has never “laid down her life” for them. Do you think I am getting to the right place here? Psychologically the children & my relation to them as a husband-less woman is my greatest worry. I don’t want Frieda to hate me as I hated my mother, nor Nicholas to live with me or about me as my brother lives about my mother, even though he is just married. I remember asking my mother why, if she discovered so early on she did not love my father, that her marriage was an agony, she did not leave him. She looked blank. Then she said half-heartedly that it was the depression & the couldn’t have gotten a job. Well. No thanks.

It is Ted’s plunge into infantilism that stuns me most. From a steady driver he has added 20 miles to his average speed, suicidal in our narrow lanes, and police summons for violations filter in week by week. He’s hated smoking as a habit, never smoked: now he is a chain smoker; I guess she smokes. I can stand a lot of things— if he were kind or wise or mature I would laugh at those things, but they are part of a syndrome. He has no idea of what he is losing in me; this hurts most of all. He is desperate to freeze me into a doggy sobby stereotype that he can with justice knock about. My sense of myself, my inner dignity and creative heart won’t have it. It is the uncertainty, the transition, the hard choices that tear at my now. I think when I am free of him my own sweet life will come back to me, bare and sad in a lot of places, but my own, and sweet enough. Do write. If only a paragraph. It is my great consolation just now, to speak & be heard, and spoken to.

With love, Sylvia