I see video games are useful to this project in two ways: first, video games are uniquely persuasive education tools, and two, video games are uniquely suited for documenting queer intervention in dominant narratives.

Although using video games for educational purposes may seem like a recent phenomena, teachers, libraries, and other public history institutions have been using analog games, puzzles, and the like to complement their teaching. [1] Video games are the digital versions of this educational practice.

However, as digital objects, video games provide a expanded capacity for persuasive teaching. Game scholar Ian Bogost contends that because video games are systems run by a computer, they employ procedural rhetoric: “the art of persuasion through rule-based representations and interactions rather than the spoken word, writing, images, or moving pictures.” [2] While other media can express complicated and multifaceted representations of the world, it does so through snapshots – two dimensional renderings of text and image. The audience looks and reads, but does not interact with the narrative. As computer-run systems with sets of rules and set interactions, video games are uniquely suited to representing the systemic structure of power, as well as how the individual player might interact with those hierarchies.

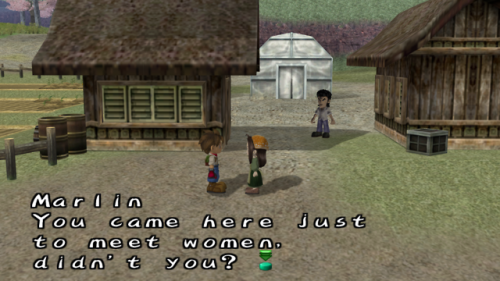

With that in mind, video games are primed for queer intervention. Scholars like Jack Halberstam have argued that the simply interaction between LGBT people as players with video games is a kind of “hacking” into hetersexual canon. For example, young lesbians like myself who played Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life took advantage of the compulsory male protagonist to romance women, exploring virtual same-sex desire in a intended heterosexual narrative. Halberstam suggests that through play, LGBT players can unearth James Scotts’ “hidden transcripts of resistance.” [3] Other gaming scholars, such as Gregory Bagnall, Naomi Clark, and Merritt Kopas assert that though games digitally mimic the power structures of the analog world, as interactive media they provide space for queer play, a process which can generate empathy for LGBT people. [4][5]

Haunted Looking is meant to recreate the alienating experience of looking at lesbian bodies, but also provide space for players to empathize with the archival subject. [ What are the problems of representing lesbians? → ]

[1] Nicholson, Scott. “Playing in the Past: A History of Games, Toys, and Puzzles in North American Libraries.” Library Quarterly 83, no. 4 (October 1, 2013): 341–61.

[2] Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, 2007, ix.

[3] Halberstam, Jack. “Queer Gaming: Gaming, Hacking, and Going Turbo.” In Queer Game Studies, edited by Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017, 187-200.

[4] Bagnall, Gregory L. “Queer(ing) Gaming Technologies: Thinking on Constructions of Normativity Inscribed in Digital Gaming Hardware.” In Queer Game Studies, edited by Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017, 135-44.

[5] Clark, Naomi and Merritt Kopas. “Queering Human-Game Relations.” First Person Scholar, February 18, 2015.