From all the books we looked at in Book Set One, De Humani coporis fabrica librorum epitome by Andreas Vesalius stood out to me the most. Christophe Plantin published the book in 1565 during the Renaissance and it is known to be one of the most influential books on human anatomy. The reason why I was drawn to it more than some of the other books was because of its cover (figure 1). I was drawn to its aged texture and faded color. If you look closely at the cover of the book you can see beautiful designs that once decorated the front and back of the book. These designs are done on pigskin, which is the material that the cover of the book is made of. When you open the book to its front page you can see the signature progression of owners that once used the book for reference and information.

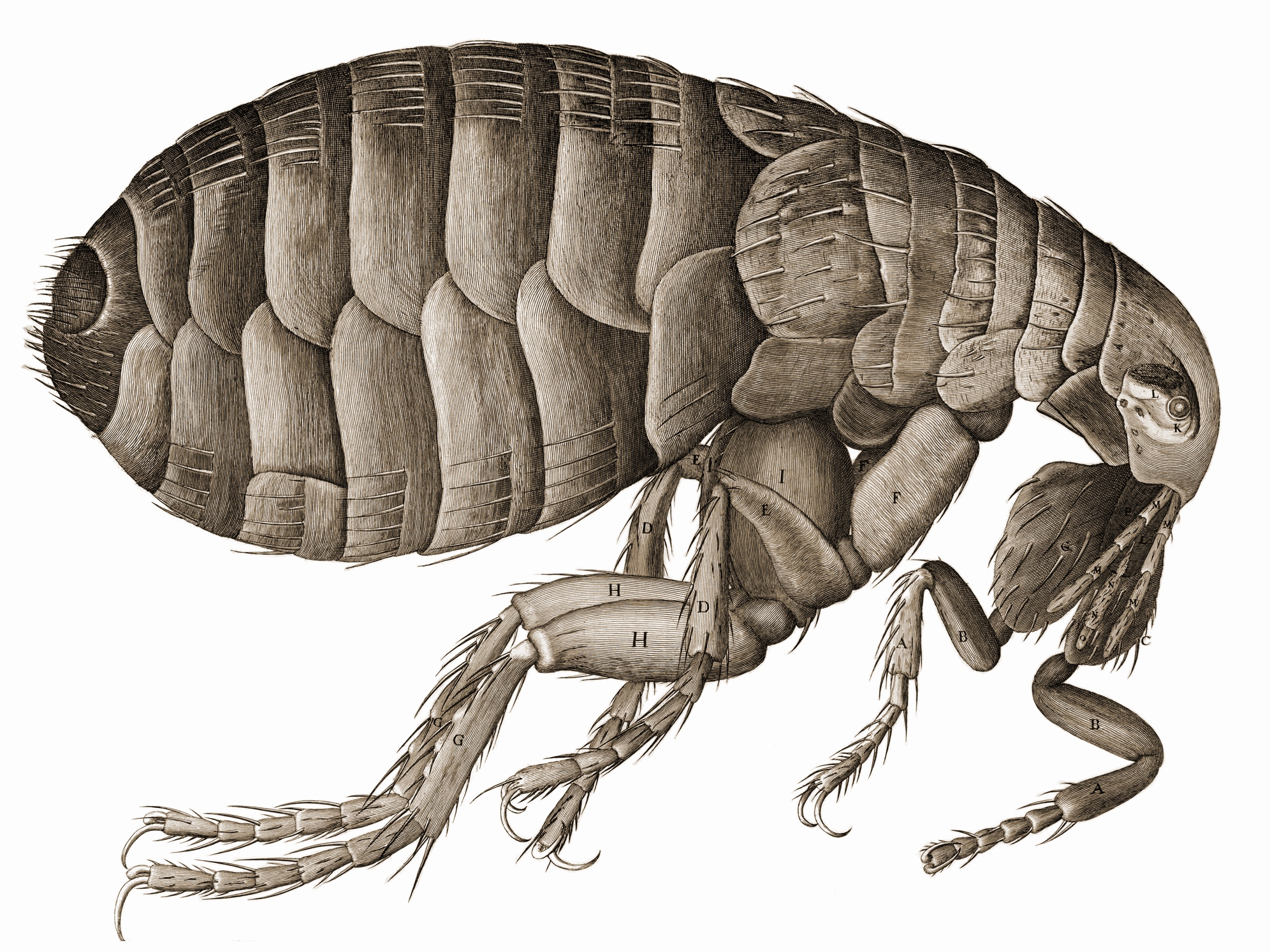

The book is based on Vesalius’s lectures in which he dissected corpses to illustrate the information he was discussing with his students. It presents detailed examinations of the different parts that make up the human body (figures 2 & 3). Vesalius was able to produce these stunning illustrations by engraving copper. The details of the illustrations make them act like beautiful drawings but also serve the purpose of informing people about the human body.

De Humani Coporis fabrica librorum epitome is laid out in a way that makes it seem like a scientific diary. The illustrations work with the text (which is a mixture of Roman Capitals and miniscule type form) using a labeling system. Each part of the diagram is labeled with numbers or letters that are then explained in a detailed description on the page next to it. Both the text and images work together to help the reader match and understand what part of the human corpse he/she is observing. Figure 4 is a perfect example of this “labeling system” and also of what the other pages in the book look like.