Wild Pilgrimage, third in a series of picture books by prominent woodcut artist Lynd Ward.

It’s a wonder to see how far the class has traveled — through time, past tradition, as the books we read veer in wide arcs from the text-heavy traditional epics of Morris to this, a work with no words. This transition is important. The book is a storytelling tool, after all, and the story usually takes the form of letters, in thick jostling crowds. A book without them is striking. Empty, even. But the image has always been an important part of the artist’s book, and it is refreshing to see it operate as a book’s major medium.

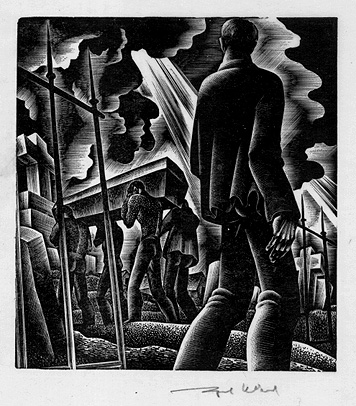

Wild Pilgrimage is, without a doubt, a book of incredible artistic endeavor. The string of woodcuts, which tells the tale of a man trying to liberate himself from an industrial, working-class society, are elaborately planned and brilliantly achieved.There is a stateliness to the book, a constrained quality — each woodcut takes up a single page, and is generally of similar size to its neighbors. Despite the riotous nature of the contents, the trappings of the book remain objective. Cold, even. And in this way, it is not so different after all from Morris’s vision of the perfect geometry, not so different from Cobden-Sanderson’s visual scarcity.

The single eccentricity the book allows itself is a switching of color palette. During the man’s fantasies, the divergence from reality is symbolized by a switch to red-orange ink, a contrast to the somber black reality is painted with. This is the most interesting part of the book in my eyes, and the loveliest aspect of it is its ambiguity — it might take several tries for the confused reader to understand that there are two separate stories being told here. Lack of words creates a silence, and silence births mystery. Everything is shown, not told.

However, beyond this singular shift, the entire book is constrained by its visual geometry. It strikes me now as an odd choice. A book with the title ‘Wild Pilgrimage’, which deals with lynchings, sexual fantasies, revolution, and violent death — these are not topics to be constrained to a square. The sharp, harsh style of the illustrations certainly match the riotous subject matter. The thick shadows and dark faces of the characters contribute to the wordless ambiguity of the story. But the format — the format reflects none of this. Should it?

Although a version of Wild Pilgrimage that escapes its harsh boundaries, that explodes across the page with the strange passion contained in its images, would very much pertain to my interests — it is important to remember where we, as a class, saw this book. Wild Pilgrimage is a book out of the 30s, but that is not the only reason it was placed with the modernist typography guides like Eine Stunde Druckgestaltung or governmental propaganda a la Italia Imperiale. They share a common format, a format that dispenses entirely with the gloss and decoration of Art Deco or the Fine Press. It is a format for clear communication, a tool for the common man, a vehicle for propaganda and public service alike. Functionality is key, and thus the format of a book, even of a wordless, picture-centric one, must follow the same constrained criteria of typography. This modernist sensibility, combined with the constraints of the woodcut medium, appears to have manifested in the strict proportions of Wild Pilgrimage. It’s an interesting example of modernism in a medium normally associated with the fine printers.

Whether this was a successful use of those tenets is too subjective a point to discuss, but it is worth noting that looking at lynchings and revolutions through the clear, unfiltered lens of modernism lends a harshness, callousness, and disconnected industriousness to the book. We have no key cards, no cues from the author about what to think or feel. It is the eye of an uncaring, mechanical world, and perhaps this is exactly what Ward had in mind.