The most strikingly and identifiably futurist books in all of the book sets were Marinetti’s Les Mots en Liberte Futuriste (1919) and Depero’s Depero Futurista (1927). Despite commonalities, the books serve very different purposes. Marinetti’s work instructs the reader on the necessity for words and freedom, and its essential elements and hindrances; the words as image are meant to teach through example as well as critique European relations. Depero Futurista, though heavily reliant on words in freedom, is rooted more in the artist than the technique. Depero’s approach to words in freedom is much cleaner and geometric than Marinetti’s, arguably less politically radical. I believe that this was an intentional choice of Depero’s, one made in part to ingratiate futurism as a movement to Mussolini and encourage him to endorse it.

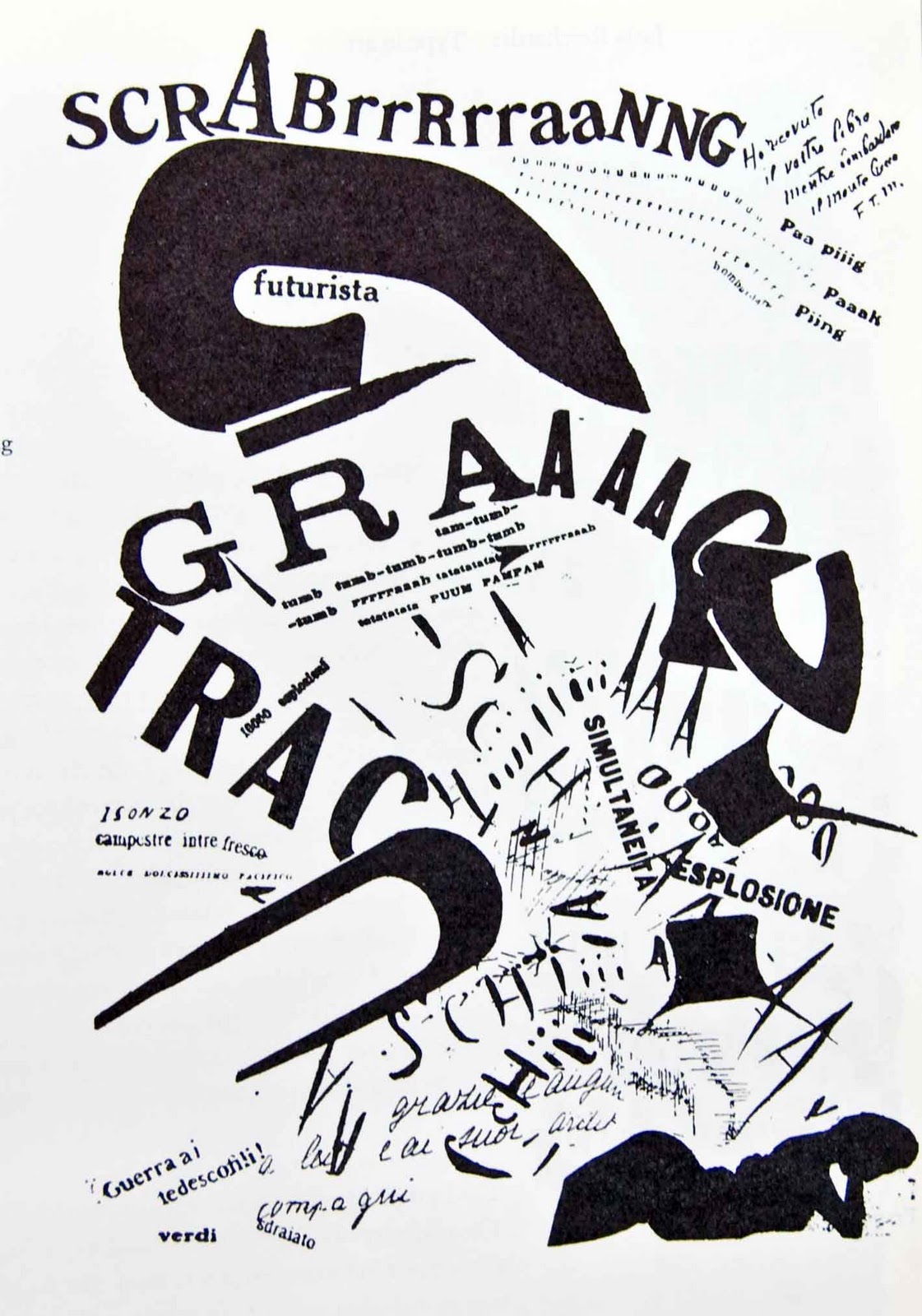

Marinetti’s Les Mots en Liberte Futuriste revealed and explained the thinking and intentions behind words in freedom, as embodied in his Zang Zang Tumb. He wanted to reduce words to their physicality, prioritizing their most primally tangible qualities; in this way, he transformed them into action. For these word-objects to be as representative of movement and action as possible, Marinetti arranged his mise en page chaotically and unpredictably. Random capitalization, sporadic bolded type, multiple types within words and sentences, a disdain for symmetry, and a general atmosphere of disorder all contribute to Marinetti’s vision of reality. They represent the destruction of traditional conventions surrounding language, such as grammar and syntax, to act as a parallel to Marinetti’s call for the cleansing burning of the past to fertilize the future.

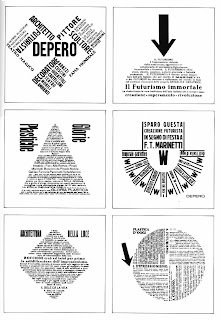

Depero Futurista, created almost a decade later, is the undeniable child of Les Mots en Liberte Futuriste. However, Depero’s use of words in freedom is much more ordered than Marinetti’s. His rejection of the norms of language are in line with his mentor’s, but his arrangement is not so arresting. Depero’s images are constructed to challenge the view but also to please; they are consistently symmetrical and centered in basic geometry. His text varies in size, thickness, and type but never with the same forceful spontaneity that characterizes Marinetti. This drastically changes the tone of Depero’s words in freedom into one less obviously aggressive toward tradition, toward Italian culture. Futurism loved fascism and sought Mussolini’s public approval from his rise to power, but the critique and dismissal of Italian tradition made it politically unwise for him to do so. Where futurists wanted to eliminate museums and and forget history, fascists wanted to return Italy the power and pride of the Roman Empire. As fascism gained influence and presence within Italy and Europe as a whole, futurists strove for endorsement through compromising the most offensive aspects of their art. I believe that Depero’s use of words in freedom was a clever attempt at maintaining the political implications of the words themselves without supplementing them with politically charged images. Unfortunately, diluting the futurist technique never made it palatable to Mussolini.