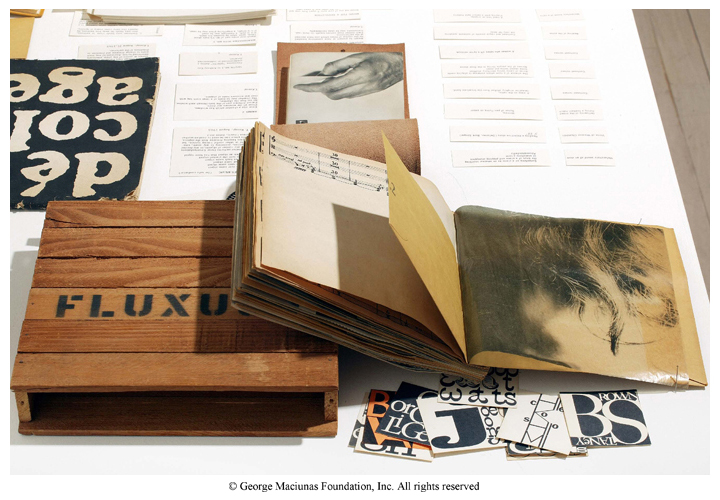

The Fluxus movement pushed boundaries in the hope of redefining the parameters of art. The aptly named Fluxus 1, shows the movement’s obsession with the collective and the varied contributions of multiple artists. Fluxus 1 is filled with instructions for how to engage with the work: “put finger in hole,” “put in 5 envelopes.” The result is a greater intimacy between reader and text. The author aknowledges the discomfort of this active exchange in his selection of bizarre images, such as x-rays of teeth and a photograph of the patch of skin behind an ear. The book is also comprised of various found objects which the audience is invited to contribute. In this way, the reader becomes author. Fluxus 1 is not written or illustrated by George Maciunas, it is “compiled and published” by George Maciunas. The artist’s role has shifted from creator to coordinator. This is also apparent in the work of Sol LeWitt, such as Arcs, Circles & Grids. It is a revolutionary concept that the artist can write a set of instructions to be carried out by others.

Fluxus 1 is not written or illustrated by George Maciunas, it is “compiled and published” by George Maciunas. The artist’s role has shifted from creator to coordinator. This is also apparent in the work of Sol LeWitt, such as Arcs, Circles & Grids. It is a revolutionary concept that the artist can write a set of instructions to be carried out by others. Among the feminist books from Book Set 10 were Treading the Maze: An Artist’s Book of Daze by Susan King, and The Dickenson Composites by Jen Bervin. The first focused on a woman’s struggle with breast cancer, and the second on a famous poet’s unique annotations and marks. These books approach intimacy from a different angle than in Book Set 9. Through their subject matter, they tell us that a woman’s individual experience is an important and appropriate subject for a work of art.

Among the feminist books from Book Set 10 were Treading the Maze: An Artist’s Book of Daze by Susan King, and The Dickenson Composites by Jen Bervin. The first focused on a woman’s struggle with breast cancer, and the second on a famous poet’s unique annotations and marks. These books approach intimacy from a different angle than in Book Set 9. Through their subject matter, they tell us that a woman’s individual experience is an important and appropriate subject for a work of art.

Book Sets 9 and 10 redefined the concept of artist and art. Art is an experience. Art is life. This new artistic realm is well explored by the Relational Aesthetics movement and by the artist Ai Weiwei. There is a fascinating documentary called “Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry” which I highly recommend. As he says: “I think my stance and my way of life is my most important art.” [youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ma6Q03ljdrg[/youtube]