I have my personal gripes about Janet Zweig’s and Johanna Drucker’s purse-lipped critiques of the artist’s book. Their approaches have many unfortunate things in common beyond sheer contrariness (both authors, for example, approach the entirely subjective world of artist books with the single-mindedness of a scalpel). But for the purposes of simplicity and at the expense of several genuinely important and well-made points from both sides, I am simplifying their complaints into a single issue: the argument between style and substance.

Not a balanced argument by any means. Style is considered the flourishy and meaningless fodder for the masses, while substance is the meat of the matter — the stuff we’re really looking for… Consider Zweig’s condemnation of “crafty overproduced luxury items” in favor of “rich temporal experiments, books that do participate in the conversations and challenges of contemporary art”. Now read from Drucker: “Overproduction is particularly deceptive since it tends to confer importance simply through conspicuous display.” For both authors, style is the shallow, preening younger brother; an early indication of staleness, derivativeness, and meaninglessness. Not a work worth liking, in other words.

With this in mind, I will discuss The WunderCabinet: the Curious Worlds of Barbara Hodgson & Claudia Cohen.

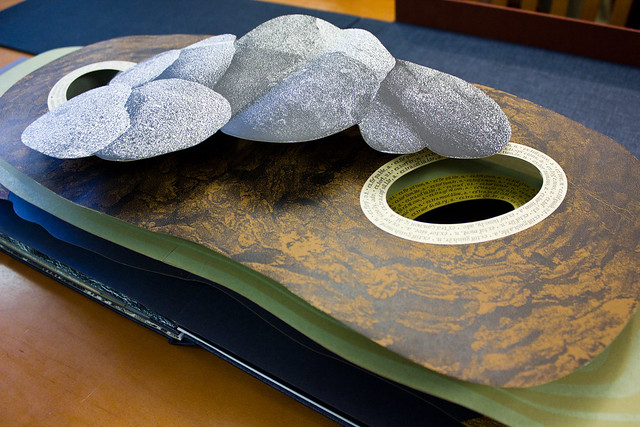

Here it is. A beautifully designed wooden box cover, containing a miniature facsimile of an antiquarian wunder-cabinet — a place in which to display your fanciful collection of foreign, exotic trinkets from around the world. Somewhere, Zweig is turning restlessly in her bed and muttering ‘crafty overproduced luxury items’ under her breath.

It also contains a journal, written and illustrated by the two artist-authors and built to resemble an old travel-journal. The writing discusses natural history, archaeology, astronomy, mathematical principles, and historically important wunder-cabinets (such as that of Manfredo Settala, a Milanese wood-turner with a collection on the sciences). However, if we’re being honest with ourselves, that isn’t what draws our eye when we open the book.

I’ll admit it, I stared at the star charts, stratigraphy plots, pressed plants, hand-inked heiroglyphs, alphabet grids, and sketches of ammonite shells first. They’re beautiful, they obviously took an incredibly long time to make, and substantively they are utterly meaningless. Unless you consider a rangy and breezy education on the contents of wunder-cabinets to be a participation in ‘the conversations and challenges of contemporary art’, of course. It would take some stretch of the imagination.

Here arises the difficulty with the ‘style vs. substance’ dichotomy. According to Zweig, an artist book such as the WunderCabinet is an object to be marveled at and then put aside. There is no deeper, richer meaning to it, nothing to return to but the same pictures and pressed plants. It is beautifully vacant of meaning, it is a dressed-up corpse — it would not be very useful on a desert island, in other words. (Neither would a novel, really, unless it tells you how to build a raft.)

But I can tell you personally that there is no other book I would rather return to. In fact, out of every artist’s book displayed in this class, the WunderCabinet is the only one I have requested to see extracurricularly; I have read it from cover to cover; if you were to give me one of the books from the Smith Collection for free, then you would be crazy, but I’d know exactly the one I’d want. It was inspiring. I took notes.

Zweig compared the experience of reading a good artist’s book to watching a good movie or excellent theatre, and I believe this is revealing. Cinema’s critical darlings may fit her criteria, but what about movies like The Avengers or Shrek? They aspire to no ideal, no high-browed message, no contemporary issue of importance. They aim to entertain only, and they have left their big-budget, cerebrally vacant fingerprints smeared upon the face of American culture while doing so. I would watch these movies again and again, but the sole difference between them and the intellectually underwhelming artist books Zweig so despises is a slightly heftier price tag.

This is a gross oversimplification of the issue, of course, yet the merits of the beautifully vacant book should still be discussed. Aesthetic beauty can inspire… Zweig compares the artist book to a narrative-driven novel, which is valid; but the artist book lies upon the bridge between the novel and the work of art, and its connection to the latter has been largely, and unfairly, ignored.