Looking back in our class, I think Les mots en liberté futuristes (1919) and Fluxus 1 (1964/65) represent many of the changes that occur through the 1900s in the book world. Les mots focuses more on typographical changes, and has some innovations in page design and reader interaction, while Fluxus takes full advantage of page design and the outside world.

Les mots, featuring text and graphics by F.T. Marinetti, takes advantage of cheap material and binding in order to reach a larger audience. It begins innocently enough, like any other mass-market book. Gradually, however, its design changes – font types shift throughout the text, and it grows larger and smaller. Eventually, words jut and slide around the page, until the text launches into Futurist poetry that stretches beyond the normal boundaries of a page. The typographic arrangement and the use of onomatopoeia create a cacophony made to awaken the common people and break the status quo in order to begin anew.

Ultimately, however, what has endured and influenced future works is the innovative typography. It has influenced much of popular culture after World War I, such as in advertising, and many artists and art movements, such as Pop Art and Bauhaus, seem to have taken inspiration from the unique design of text. George Macinaus, the ringleader of the Fluxus movement, is one of these artists (though he may not have been directly inspired by Futurism). His typography unites the diverse works that Macinaus compiled and published in Fluxus 1 (1964/65), which is a cacophony of a different sort, and further innovates the structural ideas found in Les mots.

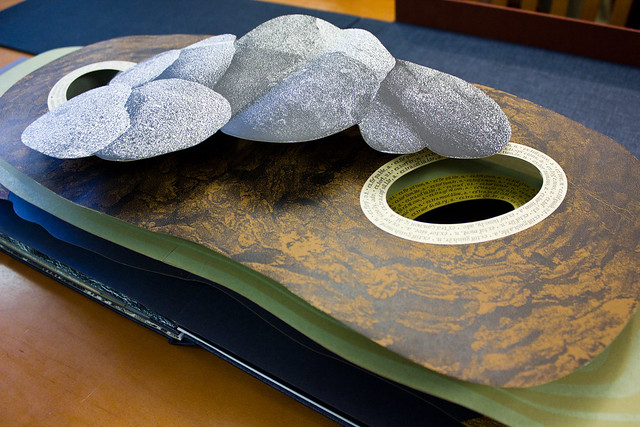

Where Les mots expanded the page by having the reader unfold them, Fluxus works to make the outside world a part of its story. The reader is invited to pack and unpack the numerous envelops in the book, pulling out different objects that represent exhibits and performances by Fluxus artists (who all worked in different ideological schools and movements). One envelope has a paper airplane, while another has some messy napkins.

But what really draws in the outside world comes near the end, with a musical opus of silence. The pianist is asked to sit at the piano, “play” each piece with the page and not from memory, and to turn the pages. The trick here is that the musical piece isn’t about the melodies – it’s about the sounds outside of the music. It’s about the ambient noise that we don’t always pay attention to. In this playful way, Fluxus 1 incorporates the reader and the space outside of the book beyond just turning the page.

Futurism and Fluxus are similar in some regards – they both share a mistrust of the concept of “high art,” and focus on changing everyday reality into something else. Futurism wanted a complete societal change by destroying the institutions around them and embracing the future, and distorted ordinary words into something unrecognizable at the time. Fluxus, on the other hand, didn’t have such grand aspirations; it’s more comparable to Dada, but with a much more tongue-in-cheek, almost innocent nihilism. Rather than destroying reality, Fluxus just brings it on the level of art.

So yeah, I think they’re pretty cool books!

Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966)

Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1962)

Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1962) Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1962)

Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1962)