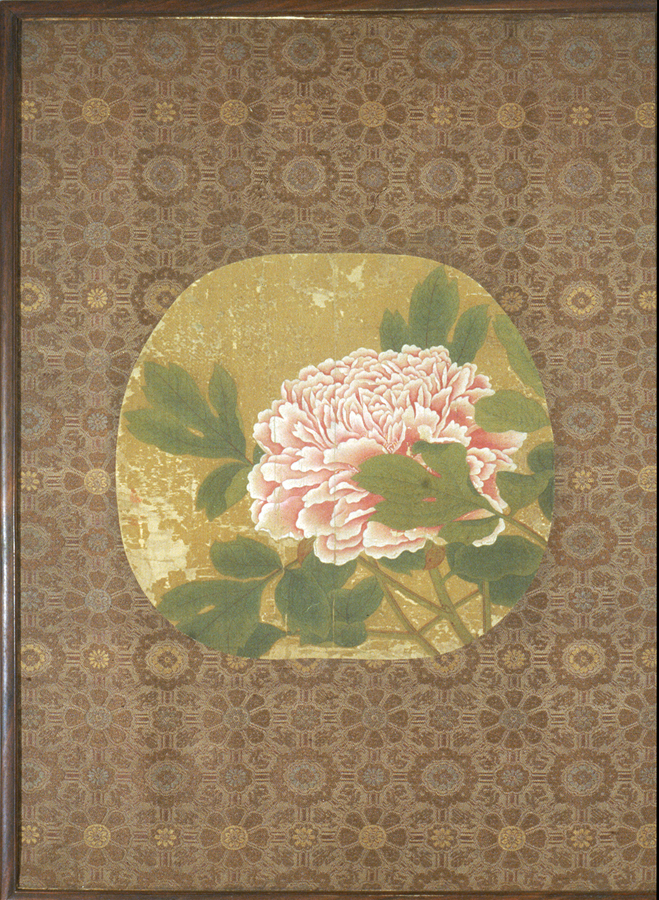

Peony Blossom with Foliage was painted in the 15th century by an unknown artist. The painting was likely painted for a wealthy family of high status. In ancient China, peonies represented feminine beauty, wealth, and the aristocracy.

Selling Tattered Peonies is by the Tang-dynasty (618–907) poet, Yu Xuanji. She is one of the most renowned female poets in Chinese history. Her poem builds on the symbolism of peonies and their ephemeral nature. Yu Xuanji’s poems frequently question traditional gender roles. Selling Tattered Peonies is no exception. During the Tang dynasty, women were required to marry while still in their mid-teens. Those who weren’t married by the end of their teens were shunned by society. The antiquated painting and poem call to mind a flower—representing a woman—that has suffered the passage of time but remains unquestionably beautiful.

Poem selection and label by Kela Harrington ’19