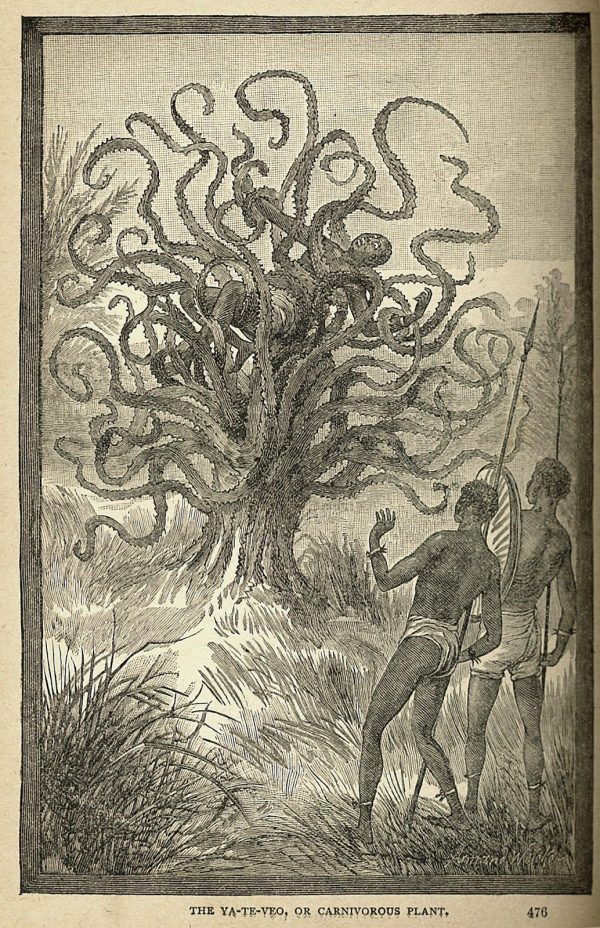

On the morning of April 28, 1874, the New York World printed an article announcing the discovery of a “remarkable new species of plant” which it referred to as “a man-eating tree.” The article described the people of the Mkoda Tribe, “inhospitable savages,” feeding a woman to this plant. The article included excerpts from a letter supposedly sent by Karl Leche that claimed he had witnessed the Mkoda tribe’s sacrifice of a woman to the tree. His letter extravagantly detailed the tree which allegedly had a trunk like an eight-foot-tall “thick in proportion” pineapple with “eight leaves… like doors swung back on their hinges.” Leche claimed to have studied the “carnivorous tree” for over three weeks. He also reported finding “several other, smaller specimens of it in the forest” and claimed to have witnessed one of them eat a lemur. In the following days and weeks many other newspapers, journals, and magazines reprinted this story.

Falsehoods like this one weren’t all that unusual. But this media hoax was unique in that interest in it didn’t die off over time the way it typically did in others. It wasn’t until nearly fifteen years later, in 1888, when a man named Frederick Maxwell Somers reprinted the story in the second issue of his magazine Current Literature, that it was debunked. Somers found “almost every detail in the story was fictitious” including all of the people who were referenced. The Mkodos tribe was not even an actual tribe. The man-eating tree was “pure fantasy.”

The only thing even remotely accurate about the story was the source it was credited to, Graefe and Walther’s Magazine. It was a real magazine. But even then there were many inaccurate details. The magazine was a real German scientific journal, but it was “published in Berlin, not Carlsruhe” and had not printed an issue for 24 years when it reportedly published this article.

After continuing to gain popularity for approximately fifteen years, it wasn’t easy to debunk this story. Somers described the origin of the story, asserting that reporter Edmund Spencer wrote it for the New York World. Spencer reportedly thought up the story when talking with some friends and realizing “all that was necessary to produce a sensation of horror in the reader was to greatly exaggerate some well-known and perhaps beautiful thing.” He wasn’t wrong about that. Despite the best efforts of many, the story continued to spread. It even led some twentieth-century explorers to search for the plant species. The first of these was an American travel writer by the name of Frank Vincent. He set out on a search through Madagascar for the species in the early 1890s. Chase Salmon Osborn, a former Michigan governor, is said to have “conducted the most extensive search for the man-eating tree.” Despite never finding the tree, he wrote a 1924 book detailing his search titled Madagascar; Land of the Man-Eating Tree.

While ridiculous, belief in a man-eating tree in Madagascar wasn’t particularly harmful. But it was important because it exemplified broader trends. In nineteenth-century America, it was extremely common for stories to spread by being reprinted in local newspapers. From news and obituaries to recipes and jokes, local newspapers reprinted segments of other newspapers with great frequency causing them to spread around, many to the point of “going viral.” This story of the man-eating tree demonstrates why nineteenth century reprinting practices were problematic. There was no fact-checking, and so small newspapers republished stories with little regard for whether or not they were accurate. They left this determination for the individuals reading their newspaper to make, but the public wasn’t adequately equipped with the knowledge and power to fact-check. This led to wide acceptance of any and all things published in newspapers. Once it was read in a publication, people didn’t second guess it, and this made nineteenth-century America the ideal environment for fake news to flourish and thrive.

On top of this it is important to realize that The New York Journal was placing pressure on The World. This rivalry “gave rise to the term ‘yellow journalism,’” the practice of employing “lurid features and sensationalized news in newspaper publishing to attract readers and increase circulation.” We now know that the New York World was not prioritizing accuracy in their reporting, but rather participating in the use of “publicity stunts, screaming headlines, and sensationalism” in order to gain “readers, staff, advertisers, and public attention.” However, at this time the idea of journalistic objectivity was only beginning to develop and the majority of the public had no expectation that “journalism” should be anything different.

The other primary reason this story was dangerous was because of its depiction of the fictional Mkoda tribe. By suggesting that they were sacrificing humans to the tree, the story painted a picture of the people of Africa as “inhospitable savages,” which contributed to the characterization of Africa as a place in need of colonial intervention. This was an additional reason why this piece of fake news appealed to people. It played into racist ideas that had long been ingrained in American society.

In addition, this fictitious story also appealed to people because, as reporter Edmund Spencer was counting on, it horrified them that something so well-known and widely considered to be beautiful had the potential to be this terribly frightening. The fear it caused in readers bypassed their reason. Without any reason to disbelieve the story, and several supporting it, it is understandable why so many people embraced this fallacy in the nineteenth century. This story is just one instance of how misleading news spread throughout nineteenth-century America. News like this spread frequently due to the nature of the media and the mechanisms of reprinting in the nineteenth century. Ultimately, this piece of fake news spread due to the lack of fact-checking practices, and the expectation that readers would verify their own news, in the nineteenth century.