By A. E. King

Entrepreneur, opportunist, and conman P.T. Barnum’s legacy was immortalized in the 2017 musical film The Greatest Showman. The main story sensationalizes his rise to fame as an entertainment legend, overlooking his exploitative nature. Instead, Barnum’s relationships and career are humanized, presenting a family-friendly look at historical stardom. On the contrary, Barnum’s empire of entertainment was built on a systematic cycle of fake news, as he manipulated and exploited mysteries, people, and society to garner fame and fortune.

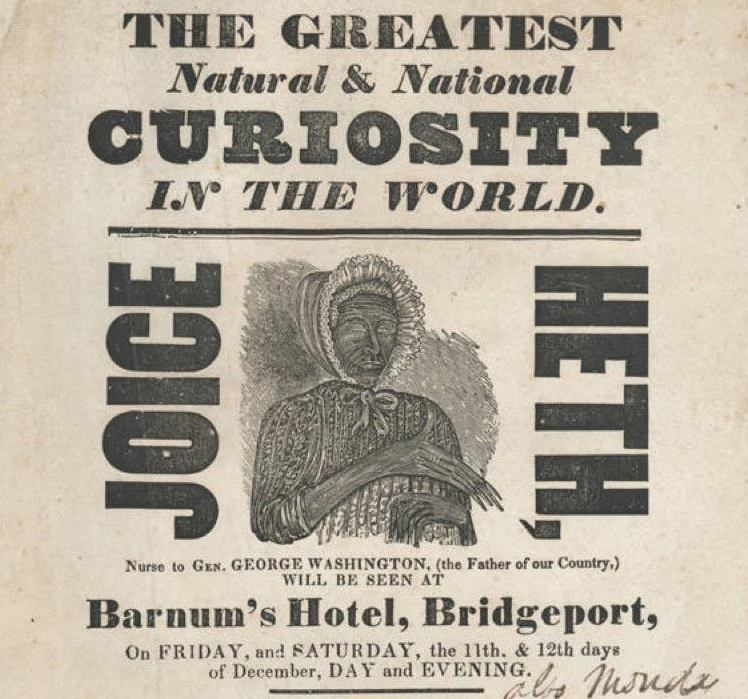

Unsurprisingly, the film leaves untouched one of Barnum’s greatest controversies, his exploitation of Joice Heth. An enslaved black woman from Kentucky, Heth was leased out to Barnum in 1835. He forced her to parade across the country as a novelty, with flyers claiming she was a 161-year-old nursemaid who cared for George Washington himself. People could pay to see her, listen to her enrapturing stories, and take her pulse. According to her coverage in the three-penny news (a cheap newspaper full of advertisement and sensationalism for the common man), Heth’s character fabricated by Barnum underwent a fantastic evolution. First, she served as George Washington’s personal wet nurse, holding him close and raising him from birth and cradle. Then Barnum “exposed her,” claiming Heath to be an automated machine made of old whale bones and leather, bound together into one convincingly humanoid form. Finally, upon her death and autopsy, Barnum spun Heaths corpse to be a mysterious body-double. When faced with the coroner’s estimation of Heth’s real age being half what he advertised (and so unlikely to be anything curious at all), Barnum accused the body of being a fake. The “real” Heth, he claimed, had apparently fled Barnum to continue performing across America. In the end, though, she was worked to death, being on display for 12 hours a day, six days a week. He even put her to work after her death. Her autopsy was a public event to the price of a 50-cent admissions rate. Every aspect of Heth’s life thereafter become punctuated by Barnum’s own rumors and ever-increasing ticket sales.

The sensationalism of Heth both in life and death propelled Barnum’s fame. The extortion of her life becoming a linchpin of pride in Barnum’s business strategy for years to come. Audiences proved to be enticed by the fantastic oddities of “P. T. Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome.” The American response to Heth and her hoax character allowed Barnum to consistently succeed in his new career.

This success evidences the love affair between profit, fake news, and the power of an audience’s infatuation toward a subject. Fake news crafts a delicate and enticing narrative, which can appease an audience by playing upon their prejudices, acting either by stoking the flames of debate or through the soothing calm of agreement.

For example, in the context of 1835 American society, Heth soothed the stress of a dividing nation through her link to a nostalgic past. Heth’s story nostalgically directed Americans to look back at the Revolutionary War, an event that seemed to be unifying in American memory. It distracted from the increasingly divisive feud between North and South that would lead to the Civil War. Heth became a link to a fading past, a way for both sides of a growing feud to look back on the Founding era with shared sentimentality. Heth’s manipulated story and character thus becomes evidence of the fake news love triangle. The public excitement and willingness to buy into her myth explains the growing need for communities to re-affirm their faith in their nation, and to be comforted by familiar stories of their once great past.

One aspect of contention in Barnum’s controversy was his abuse of people of color, and how white American society created the opportunity for Barnum to fabricate and subsequently sell his lies about minority performers. Heth’s attraction, the air of mystery surrounding her, was that she was old and could spin a good tale. This was not necessarily odd for a white woman, but as a black slave, Heth was already set apart from the white audience. Heth was Barnum’s perfect exploitable act. Her unifying stories drew people in, while her separate class and appearance kept her mysterious.

Her status and rise to fame, therefore, encapsulate the thoughts of Americans at the time, where people of color, specifically black Americans, were more susceptible to being designated as an oddity. This would then allow for the reinforcement of misinformation and nefarious profiteering from such fake news. Other similar cases in Barnum’s circus were African-American William Henry “Zip the Pinhead” Johnson, who was kept in a cage and displayed as a missing link between Africans and orangutans, and two “Aztec Children” named Maximo and Bartola who were paraded in human zoos and Barnum’s American Museum. Each of these fake news stories thrived on perpetuating racism, where the “otherness” of racial minorities and genetic diseases could be exploited.

In the end, the sensational story of Joice Heth is a time capsule, giving us an insight into 1830s American society. The public’s response to her story reveals the need for confirmation of internal beliefs. The threat of a fast-approaching civil war divided the political horizon, creating a black hole of doubt for the nation’s strength and fortitude. Heth’s show reminded many of America’s founding fathers, thus distracting and reassuring audiences with nostalgia. The show was empty yet affirming. Similarly, her abuse by Barnum and the nature of her life gives similar insight into the reality of race-driven politics and societal norms. The exploitation of Heth, and her presentation as sub-human along with Barnum’s other minority acts shows the racist reality of the 1830s, and the disparity of treatment between different social classes.