A philosopher’s answer to a double question: What are identities and why do they matter?

“What are you?” Whether in my home town of New York City, or in various countries around the world — Italy, India, and the Caribbean, and so on — I have been asked that question by many. Indians have guessed that I am Dominican, Ethiopians have guessed that I am one of them, Egyptians have thought that I’m Egyptian, Arabs have guessed that I am Arab, and African-Americans have asked if I’m American Indian or Japanese. If there is so much confusion about what ethnicity I am, based on my appearance, is racial identity really real?

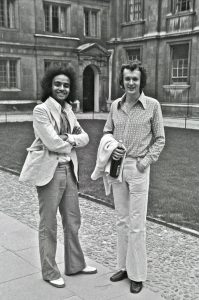

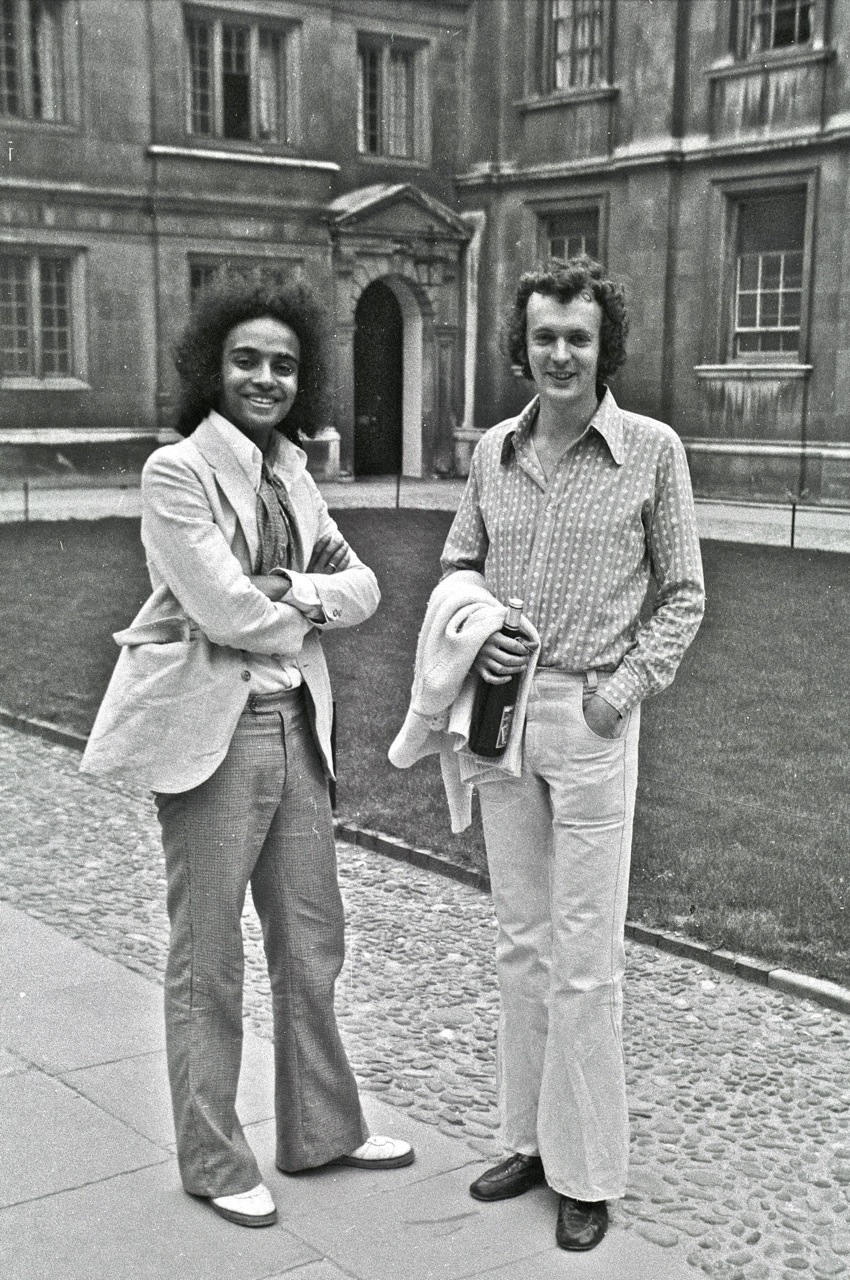

It turns out that Kwame Anthony Appiah, a celebrated and award-winning philosopher, New York Times columnist (The Ethicist), and professor at NYU, has experienced a similar narrative throughout his life. As a mixed-race person, he opens his book, The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity (2018) by recounting that taxi drivers all around the world have tried to guess “what” he is based on his appearance and accent — although they usually ask him this with the less blunt question, “where are you from”? Even I, when I saw Appiah speak at Smith College on the subject of identity, wondered to myself — what is he?

Leaving this question unanswered, or simply answering “I’m human,” or in Appiah’s case, saying he’s from London, is not enough to fulfill one’s itch to know how someone identifies. The taxi drivers wanted to understand why he spoke the Queen’s English, and what ethnicity he was, behind his brown skin. This itch is what makes us try to identify others before they even tell us how they identify themselves. Or even when someone does tell us how they identify, we make assumptions based on what they tell us, which leads us in the wrong direction. Identities can also unite us; in my high school several Indian international students visited my global feminism class, and we were united, although of different nationalities, by the global feminism fight, with which we each identified. Or when I was studying abroad in China, I became friends with students from Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, because we were part of the black minority on campus and in the country.

So, while emphasizing that identities are not inherently bad, Appiah wants to argue in his book that they don’t inherently exist. Despite how it may naturally seem to us, there is no essence of identity: “existence precedes essence; we are before we are anything in particular.” Making mistakes around identity can be extreme. We identify ourselves, we identify others, even when we don’t want to, and we are identified by others in some way, even when we don’t want to be, and sometimes in ways that we don’t want to be. For example, “Race has been a source of trouble in human affairs … Too many of us remain captive to a perilous cartography of color.”

According to Appiah, there are 5 main species of identity today: creed, country, color, class, and culture, that are “the legacies of ways of thinking that took their modern shape in the nineteenth century.” He dedicates a separate chapter to each one. Throughout these chapters, Appiah explores how each species of identity relates to the others, and how they have come about. According to Appiah, it is important we engage in these discussions about identity that will help us get to the truth of them, if we “if we are to live together in concord.” Appiah’s philosophical approach allows him to sincerely humble himself to the reader–he’s not above the subject matter–and it allows us an open space to walk into and explore these ideas, almost like a guided tour by him, with narrations, historical examples, and interesting claims hanging all over the walls–a journey into a world where we are comfortable with him and can use our own minds to think about what he’s saying, not just totally disregard it if we disagree, or passively accept it if we agree.

Appiah has an insightful cosmopolitan view, which, although not usually explicit, underlies the whole book. After all, he is the author of Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in the World of Strangers (2006). In the last chapter of The Lies That Bind, entitled Coda, he writes, “The cosmopolitan impulse that draws on our common humanity is no longer a luxury; it has become a necessity.”

A place where I found myself uncomfortable was in the chapter Culture. Appiah believes “we should resist using the term ‘cultural appropriation’ because “all cultural practices and objects are mobile; they like to spread, and almost all are themselves creations of intermixture.” I can see how this fits in with his cosmopolitan view — of course ideas, clothing, foods, and so on have traveled and intermixed with other cultures and have created new things. Appiah believes the problem with the issue of cultural appropriation is that “the very idea of ownership is the wrong model.” As someone who believes him when he says identities cannot be owned because they don’t have essences, I understand his point. Yet I’m still grappling with the fact that I feel uncomfortable when I see white people wearing braids or dreadlocks, which is a common example of the hot and sensitive topic cultural appropriation is in the United States today. Part of me feels that white people shouldn’t do it, because they’re not respecting, or are “taking” something for themselves, while people are fighting for laws against discrimination against black people wearing them in the workplace. Appiah, can you help me sort this through?

Appiah’s book nonetheless leaves me with a freeing feeling. It has helped me let go of my own identities, or at least see them as illusions, so that I am not attached to them. When people get my identity wrong, or if people assume something based on how they identify me or how I’ve identified myself, I am more capable of not getting upset, or even prideful, because it’s all a complex and changing illusion, a game of appearances.

This approach to identities can also be freeing because I can identify as anything, and identity becomes a fluid thing, but a thing nonetheless. Anyone can be anything, because that’s what we are from the get-go — beings, question marks. Then the question “What are you?” is revealed to be more profound, perhaps unanswerable.