A Response to the “Labels are for Soup Cans Not People” Mentality

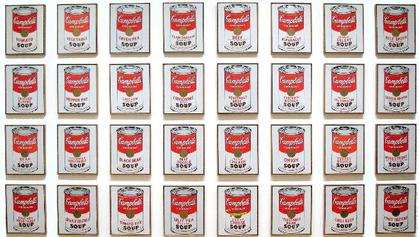

The worst bulletin board I’ve ever had the displeasure of seeing in the halls of my high school featured an array of Campbell’s Soup cans and the pithy phrase “labels are for soup cans not people.” Each construction paper can stapled up on the crinkled blue backdrop featured a label, among them – gay, fat, and nerd. I think that I was supposed to take offense to these terms, and get the impression that I shouldn’t use them to describe other people. I just saw myself. How, I thought, could the well intentioned bulletin board makers get it so wrong? I’m not disagreeing with what I take to be their underlying point: labeling other people and reducing them to a singular aspect of their being is wrong. I am just as upset as anybody else when identifiers are used as terms of abuse. But, identities and labels aren’t inherently bad! I didn’t get how anyone could completely discount the joy and unity that come with finding another person who shares your identity, who labels themselves the same way. I know that when I was struggling to understand and come to terms with my sexuality I felt less alone when I found the words to describe my attraction. Having the language to talk about my self helped me find both resources and community.

Now, every time I see a debate about identity politics I think about that bulletin board. And I think of two of the ways we can choose to see identity, as something that separates us and alienates us, or as something that brings us together, sometimes powerfully, in efforts to organize for our collective needs. Unfortunately, I have found that most commentary on identity follows the first route to the complete neglect of the second.

So, when I picked up Kwame Anthony Appiah’s The Lies that Bind: Rethinking Identity I was primed to be disappointed. I was pretty sure, from the title, and the prominence of the word ‘lies’ in it, that Appiah was going to dismiss identity outright. He calls them lies after all!? But, I was pleasantly surprised. Appiah offers an incredibly careful and measured approach to thinking through identity. He chooses to see value in it, highlighting the way that identities unite us and make it possible for groups of people to do things together, while also attempting to levy a critique.

In each of the six chapters in the book Appiah argues that we often fall into the error “of supposing that at the core of each identity there is some deep similarity that binds people of that identity together. Not true, I say; not true over and over again.” Take national identity, for instance – in chapter three “Country,” Appiah turns to cases that push our notions of national identity. From the complicated national identity of one writer, Italo Svevo, to the story of an emerging national identity, and its plurality, in Singapore – Appiah labors to show, “the truth of every modern nation is that political unity is never underwritten by some preexisting national commonality. What binds citizens together is a commitment … to sharing the life of a modern state, united by its institutions, procedures, and precepts.” National identity, doesn’t pop up fully formed, it’s invented and continually reinvented.

That brings us back to the crucial insight in Appiah’s title; identities are lies; they are things we construct and make up. They are not necessary facts of our lives, they are things that exist and come to be important because of the circumstances of our lives. But, the fact that identities are constructed isn’t grounds to dismiss their importance. They can crucially inform our views of the world. “Identities work only because, once they get their grip on us, they command us, speaking to us as an inner voice; and because others, seeing who they think we are, call on us, too.”

Appiah is suggesting that we ought to accept that identities have import in our world while recognizing that they do a poor job conveying information about beliefs. Identity cannot, Appiah emphasizes, stand in for discussions with other people. You can’t know someone’s beliefs from knowing how they identify. I think we all make this mistake sometimes – I certainly have. I tend to believe that other LGBT+ people will support more liberal policies, and I am frequently proven wrong. Twinks for Trump, and their viral campaign featuring shirtless gay men wearing Make America Great Again hats, was prime evidence of that folly. If I had taken the approach to identity that Appiah suggests, I never would’ve made that mistake, because I wouldn’t have assumed anything at all upon knowing one of someone’s identities.

Appiah suggests that we talk with others and let them tell us what they believe for themselves, without making assumptions. Right now, he says, we are giving up chances to find common ground. Some Republicans and Democrats may agree on some policies. They could work together, making progress in a mutually desirable direction. This portion of Appiah’s thought strikes me, personally, as overly optimistic. I can agree that it’s best to let people identify themselves, and articulate what their identity means to themselves. Yet, I find that political identity, tends to be pretty reliable in giving me a general sense of what other people believe. After all, there is a reason why a person chooses to align themselves with one group or another. Even if they don’t hold all the beliefs that their party does, they are letting you know that their priorities lie in that direction. Is the issue really as simple as a lack of communication? Or is it something more difficult, like a clash of values?

Despite my misgivings about Appiah’s incredibly hopeful tenor toward the power of conversation in healing divides, I found this book to be a valuable read. It is carefully argued, brings in a variety of examples, and has a very approachable tone. Mostly, though, I liked the book because it was nice to see someone holding proper respect for the ways that identities work in our lives, not merely suggesting that labels ought to be left to the soup cans.