The Musical Life of Lakshman Iyer

Shay Iyer ’23

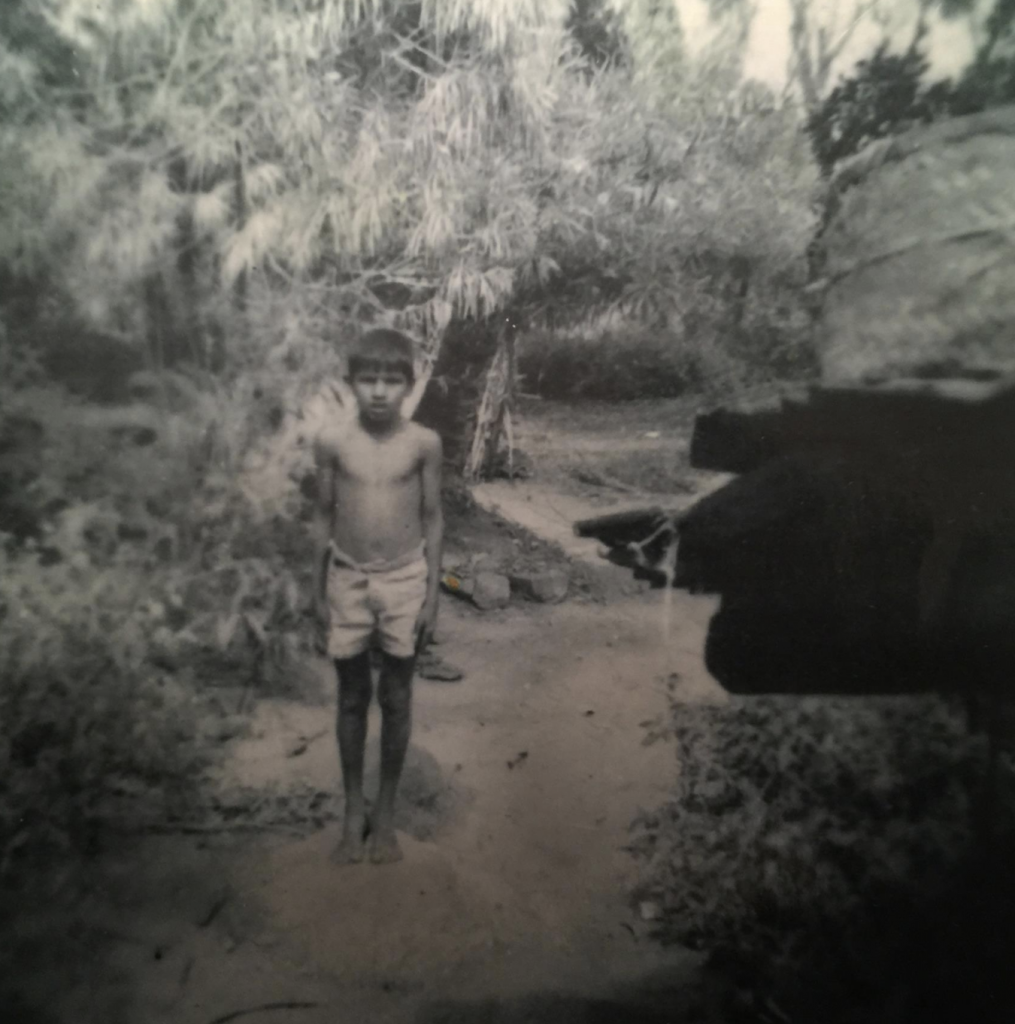

My life is littered with stories. I grew up on the works of J.K. Rowling and Lemony Snicket, tales of magic and misfortune, and heroes that seemed almost intangible. Fiction was my bread and butter, but no make-believe story ever matched the stories my father told me of his childhood. Dad has always been happy to share stories of the antics he got up to. There was the time he fell and slashed his nose on a jagged rock in the middle of his village, leaving behind a jagged scar that I cannot picture his face without. Pouring fresh kaapi into a mug was always accompanied by the story of how his father would bring him the same sweet Indian coffee brewed by his mother as he slaved over his textbooks in college. Every moment in my father’s life now brings forth old memories; every bedtime story was a fond reminiscence; every chiding life lesson passed down to me was earned from my father’s own experiences.

As I aged, however, I realized that the timeline I had crafted for each of these tales was all wrong. Every little yarn was tangled into a Gordian knot that I had no way of undoing. When I finally left for college, I realized that I needed to sort things out. So when the time came for December break, I gathered every question that had been looming in my mind since the first story and set out to sew my father’s story back together.

The process of interviewing, like every other moment we have shared, came organically to my father and me. As we made ourselves comfortable in my sister’s bedroom (a small space that once, back when computers absorbed a whole room, served as Dad’s home office), the conversation adopted a natural flow. Were it not for my asking him to state his own name at the start of our interview, the next hour would have seemed to anyone like an average conversation between the two of us.

Shay: So, the first part is just a formality, so can you just tell me your name, when and where you were born.

Lakshman: My name is Lakshman Iyer. I was born in the year of 1966, in a small rural village called Karumanasery in the state of Kerala in India… in Asia. It’s a small settlement of Iyers; that’s the community that I grew up with. And I grew up in a small village up to my seventh grade, after which I migrated to Bombay with my family. I was there in Bombay until I entered my Master’s studies, when I went to IIT Bombay. Subsequently, I went to Indian Institute of Science Bangalore to do a PhD, and at the age of around 28, I came to U.S. to do my post-doctoral experience and subsequently settle down here.

Dad’s life revolves around education. As a lifelong scientist and philosopher, he claims that he had been asking the big questions— “what is it you’re trying to do in life? What is the purpose of the whole thing?”— since he was two years old. It was fitting that his tweet-length description of his life’s journey was marked in time by his grade level and educational experiences. What fascinated me, however, was his use of the word Iyer, our last name, to describe his community growing up.

S: Okay. So when you said settlement of Iyers… what is the significance of the last name Iyer?

L: We are Hindus, and Hindu Brahmins. In the Hindu Brahmins clan, there are two vertical divisions: the Shivites and the Vaishnavites. Shivites believe that Shiva is the supreme lord, and Vaishnavites believe that Vishnu is the supreme lord; when I say supreme lord, I mean that their prayers are devoted to these lords. We belong to the Shivites, and of the Shivites, we are the type from South India; we were just called as Iyers. It’s a very generic last name, and it basically means “Shivites from South.”

Prayer was the foundation upon which every schedule, activity, and moral compass in Dad’s village was built; it comes as no surprise that prayer served as the foundation for Dad’s musical life as well.

L: So I grew up in this village which was very homogeneous; just Brahmins, one caste. So when I was very young, our whole life revolved around the temple. And my father happened to be the priest of the temple. He was the religious head of the temple. And when I say our life— our entire life. Every day we would get up in the morning, take a bath, almost everybody would go to the temple, pray in the morning, and then go about their business. Go to work, or go to school, or something, come back… and even in the evening, everybody will go, take a bath in the communal pond after they come back, and they’d pray.

These prayers were beautiful sessions, sometimes even lasting for hours. He recounted their weekly panaka pooja, taking place on Friday nights, where people would pray for hours and simply enjoy their time together. The rigidity of this schedule sounded, at first, almost stifling. However, I soon learned from my father that his initial memories of religious music extended beyond regular daily poojas, rituals, and bhajans, devotional songs. My father’s eyes shone with reverence as he detailed his village’s annual festivals; in his brief explanation of the music, I could hear traces of excitement from his boyhood.

L: There were percussion instruments that were played when the procession took place, and the songs all had different tempos, and different raagas that were played… there were different types of instruments that were played, it was a community effort, and everybody took part in it. This was a few hours, so we could sit and enjoy it; I get my sense of rhythm and music from that also. And all marriages, most importantly, in our community involved instruments, tabla and nadaswaram which played very traditional music. Any time there was a religious ceremony, it was punctuated by so many people playing very traditional, beautiful music.

Having experienced a taste of these traditions myself at temples here and in India, I felt the unspoken emotion in my father’s words. No amount of his trademark hand gestures and animated speech could do justice to the feelings of being in the middle of a Hindu festival. The drum beat echoes within the chambers of your heart and rib cage, so strong that you physically shake with each blow; the resonance of a nadaswaram (an oboe-like double reeded instrument that produces a bright melody) fills your head with its tinny buzz; the raaga, a concept which can best be equated to a mode in Western classical music, conveys an emotion that drives your heartbeat to start following the rhythm of the drums. In these festivals rhythm is, as my father accurately states, “ingrained into you.” Later on, he remarked on the natural tempo of the human body, something that made me believe the vigor of these festivals and poojas etched a sense of rhythm deep into his soul. “That is where my whole introduction to music started… where my regular feeding of music began,” he explained to me.

My father is not religious. He believes that anything you cannot prove is not worth trusting, and that knowledge and Self fuels human progress rather than a God who can grant miracles. Even so, prayer stands as the core of his musical life. It seemed to me that the true experience of prayer for my dad, a young boy growing up in a village, revolved around the people he shared those moments with. Community was a norm in my father’s life for as long as he lived in Karumanasery. From his stories, I learned that the village shared music as a way to share knowledge between generations.

L: In the villages, it’s very funny, correct? In the morning, there was this tradition that everybody would study, do their schoolwork, come out right to the front of the house, and shout out and sing. Everybody would be singing there. I remember my elder sisters and all the older people learning poems and reciting out poems about those beautiful big flowers that would be standing shoulder to shoulder and putting all this pollen out. They’d always sing these poems and you hear it all the time and it just gets ingrained into you. These poems would be sung in proper meter, taught in school, because the poems were like that. And because it was a village, everybody openly sang them, and you learned from them. That’s another place where you got music from. We were always surrounded by music.

He noted that this music existed for a separate purpose, for something other than devout worship. These were generally “the only let go’s” the villagers of Karumanasery had; movies were generally too expensive and there was only one radio in the entire village. Granted, this radio was not put to waste. My father reminded me that he still got to listen to the popular music of the year; when the one radio was switched on, he and the other children got to listen to the “film-y songs that would come on for half an hour.” But these were not such an important part of his life. Spending his formative years surrounded by a religious community had ingrained Dad with a deep love for culturally driven music, be it religious prose or classical poetry. Bollywood pop music would never hold as much significance as the bhajans that were the first and last part of my father’s day for 13-odd years, the verses he would listen to his sisters declare loudly into the muggy heat of the afternoon, or the small celebrations that filled every day.

L: The coming of age of girls, that was also celebrated… big time! Some of the songs were… not very nice. They sang about how when a girl comes of age, she will develop a crush on this guy… some of those songs were very rowdy. But only the older people knew, and they were never written down. It was just handed on down. And the young kids were not allowed to listen to them, it was the tradition.

Cultural norms were pervasive in this community; it was obligatory for young women to learn to sing, and men were the ones leading prayer chants every day. My father learned some of the Vedas, Hindu religious texts which are taught explicitly orally, from his father, who had learned from his master when he was training to be a priest, but these prayers were not entirely musical so much as they were rhythmic. Learning Carnatic (South Indian classical) music was still a luxury reserved for those who could afford it. My father’s family, while of high caste, made very little money due to his father’s profession as the village priest, so music was taught to his sisters by their mother and grandmother. This was a generational tradition if you had singers in your family, but if not, people would have to find a way to learn music.

Even though they could not attend Carnatic music classes with teachers, my dad fondly remarked that both his parents had a passion that did not stop them from learning. He recounted that his mother, my grandmother, learned music by sitting under the window of a rich child who was learning music lessons, and discovered her own love of Carnatic music later. This is something that he did not discover until his 30s, when she began singing along perfectly to Carnatic music that he had been playing.

Even his father, a generally stoic man who reserved words for only the most salient of moments, had tried to learn carnatic music. He had apparently heard kacheris, concerts, and had attempted to run away from home; however, because he could not afford it, he was made to return home and continue his training to become a priest. He could never learn music, but it did not mean that he couldn’t sing.

L: He had an incredible sense of music. He would lead the bhajans… and he was a very good singer. A very good singer. Oh my god, he was such a good singer. And even before the main song, there used to be some prayers, and my dad used to sing them very well. Beautiful prayers.

To Dad, the beauty of a song does not simply lie in the technicalities of composition. It was my grandfather’s bhavam, or emotion, that encouraged Dad to call those prayers beautiful.

L: For most people, God is something different. But my dad worshipped and took care of the God, the idol, for 20 plus years— we had to wake up at 3:30 or 4 in the morning, get in the cold, take a shower, take the water, my dad would go, wash the idol that’s 3, 4 feet, clean it neatly, then dry him, then dress him up, decorate him, feed him, and worship him. So for my dad, when he said Krishna, yes it was the lord, but it was the Lord he took care of. For him, the Lord was another person. When my dad sang, he sang to something real.

Bhavam is a concept that Carnatic musicians spend years trying to master, but it comes as easily as breathing to those like my grandfather and father. Just as my father learned poems and traditional songs by listening to his older sisters or the older members of the village, he learned how to “sing to something real” from his father. The sheer emotional power of song was ingrained in his early musical life, a theme that carried to his young adulthood when he unlocked a new appreciation for music.

L: Until my PhD, I didn’t do any music. I would listen to bhajans, to music, but I never sang. I never sang for my life until my PhD. So when I went to my PhD, fortunately my roommate happened to be one of the greatest mridangam players in India now, actually. Vaidyanathan. So he was my roommate, turns out that his uncle was one of the guys who won the top prize in India for carnatic music. So this guy, he was a mridangam player, mridangam is a percussion instrument, drums that they play. And he would sit and practice every day, even now he practices every day, and then it rekindled my interest.

As per honorific traditions within the Indian-American community, I know Vaidyanathan as “Vaithy Uncle.” The last time he visited my house, he carried a small drum, surface made of a stretched lizard skin; he never wanted to miss a day of practice, and his incredible skills are to show for his hard work. He was and still is deeply dedicated to his craft, and it was with him that my father’s PhD experience became such a huge part of his musical life. The small, closed community of Karumanasery had given way to the bustling city of Bangalore, Carnatic music filling the temple concert halls every sunday.

L: Every Sunday, in the temple, in the street, there will be a concert so we will go every Sunday. And that is how I got into that music. And it was free, so I listened to the top artists without paying a penny. And many of the times there will only be 20, 30 people in the small hall, we were just listening to all the stars right there. So that is how I understood all those things. I listened to some great people.

Carnatic music is not a genre that begets instant adoration; it is harsh and confusing to the ears at first. When my father exclaimed that he used to think Carnatic music sounded like a “donkey braying,” I immediately pointed out that my sister and I thought the same when we began learning it. We fondly thought back to the car rides where we would incessantly mock acclaimed singers on CD; I always thought it odd that my father reacted to our antics much less than my mother, who would angrily reprimand us for making fun of such beautiful music— and giving her a headache. In that moment, I realized that my father and I shared the same music experience. The formal Carnatic lessons I received growing up served the same purpose as Dad’s time going to concerts with Vaithy Uncle: they were both ways for us to understand the art properly.

L: Carnatic music was something that I never understood at that time because nobody taught me anything properly, so I thought it was all like a donkey braying. That is what happens with carnatic music. It just takes some time to learn and listen, and then get into it. Now I can understand when a note goes on for a long time, I can hear the ragam properly. After time, you can get the beauty of it, all music, you can notice how universal it is.

His appreciation for this craft carried on for the rest of his life. He continued to listen to Carnatic music, finding beauty in the works of famed singers like Madhuri Somu and great composers like Tyagaraja. He explained that he loves Tyagaraja’s music because “when Tyagaraja wrote, he wrote with his heart out.” He even expressed that he only listens to Madhuri Somu’s music for the raw emotion that can be heard in every word; “it’s amazing,” he remarked to me, “if you know the language you can actually see the people, how excited they are!” There was no difference in joy from when had spoken about his father.

For Dad, social hierarchy does not exist. He often finds formalities inconsequential, showing up to conferences in plaid shorts and Hawaiian shirts (attire that drives my mother insane), preferring sandals in summertime over fancy Sperries that pinch his feet, and addressing everybody by first name. It was no surprise to me when he equated the emotion found in two of the greatest musicians in Carnatic history to that of his own father’s; if anything, it showed me that he sees an equalizing humanity in everybody. When I asked him why he believed music should be a part of our lives today, he expressed an idea that confirmed my belief. “Music, kunja, is the core of our culture. Human culture,” he said, speaking softly and using an old Tamil term of endearment. “In music, you can express many things. Music has the ability to appeal to our emotions, and that is very important. If we don’t have that, what separates us from the rest?”

This value cannot be taught in schools, even from the best teachers. Understanding that music is the pinnacle of human creativity stems from innate curiosity— one that my father had always possessed— and a willingness to listen. It was listening that started his musical career, and listening that has kept his passion alive for so long. Listening to the poojas that took place every day, the raunchy songs or metered prose in the afternoons, and vivacious kacheris in the temples of Bangalore all taught my dad an appreciation for the ability to craft music. With this idea in his mind as he traveled to America to start a family and further pursue his education, Dad’s music branched out.

L: For quite some time I was addicted to jazz. I used to just listen to jazz. You know, Jazz for the Asking, NPR, I listened to it for quite a long time, and then I used to listen to… of course, Tom Lehrer. Who can forget that. For some time, I was hooked onto Bob Dylan, because it was in some cassettes I got. And I was always interested in blues. I used to listen to some blues also.

If anything can come close to the rhythmic intensity of Carnatic music, it would be jazz. I have vague memories of car rides with Jazz for the Asking playing in the background, my dad scatting along in the driver’s seat just like he would with a particularly upbeat mridangam verse. Pondering a little, I figured that jazz improvisations of artists like Kenny G parallel the akarams of Carnatic music, complex improvisational runs by vocalists made up on the spot that somehow always meticulously stay within the notes and signatures of the raaga perfectly. I realized why my dad was so enamored by jazz: it shockingly mirrored Carnatic music. In the same vein, blues satisfied my dad’s craving for a steady pacing and rhythm that carried the song. It was interesting that both of these genres had deep roots in African American culture, used historically to tell stories of overcoming oppression, discrimination, and strife. It was as though my dad was drawn to the raw, wordless emotion of jazz and blues the way Madhuri Somu’s bhavam drew him closer to Carnatic music. The same could be said about Bob Dylan, who was famously involved in the Civil Rights movement. While his words were not always explicitly directed towards the hatred that plagued the country at the time, the power of his sentiment shines through in his compositions. My dad’s long history of hearing music from the most dedicated singers and musicians had left him with an internal magnet, drawing him closer to the values he had built as a young child. What stood out to me, however, was his choice of Tom Lehrer’s music.

Lehrer was a mathematician turned musical comedian, and his music targeted a hyper-specific niche that my father happened to fall in perfectly. A scientist in profession and comedian at heart, my dad’s wheezing laughter could fill our car in an instant on long rides to New Jersey as Lehrer’s “Poisoning Pigeons in the Park” played on. His laugh has brought my mother and I to tears from laughing at how much he enjoys the music. Listening to our interview for the umpteenth time, I finally recognized that beyond emotion, my father values music that occupies space in your mind. His music has always made me think or feel so deeply that it overtakes my entire being, and rarely have I ever seen him listen to a song without fully appreciating it. In fact, he claims that truly understanding the meaning of prayer and music is a journey that eventually prompts deep philosophical thought.

L: Guru Nanak ends the song by saying, “there is nobody else but you.” In this world, the only thing is you; you have to find truth. Roughly, this translates to “in this world there is nobody who is yours.” But the interpretation to me is that “in this world, you have to realize yourself. You have to look at yourself and realize.” That idea of Self, that spirituality, that is the whole Indian philosophy.

That is what the Upanishads say, right. Tadh twam asi. “It is you.” So this is the beauty of Indian music; it goes to the root of the problem. The root is Self. Self-awareness. Introspection and to make your life something.

Here, I learned that it was a deeply rooted appreciation for culture that allowed my father to make these connections. The philosophical stories within Hindu epics are, in some ways, treated the way children treat Bible passages in Sunday school. They are learned, memorized by heart, and then truly absorbed into the mind as time goes on. However, this culture needs to be introduced to a young mind in order for them to develop a sense of virtue later on in life.

Perhaps this is why my dad was so insistent that his children learn Carnatic music in America; we would not have the safety net of an entire village to catch us when we fell, but at least we would have an important piece of our heritage to guide us. Learning Carnatic music, at first, was a chore, but he and my mother demanded we stick with our teacher, Tara Anand. A world-renowned Carnatic educator, Tara Aunty had eyes that could pierce through your soul and freeze you in your seat; she taught with rigidity and structure, and did not take well to mistakes in the least. But thanks to my father’s insistence that I continue learning music, she became one of the most important influences in my life, and singing Carnatic music became one of my favorite passions.

L: Yes. Carnatic music is a great tradition. It is something that was passed down to us. And that is a piece of tradition that we immigrant Asian parents want to pass to you. One of the traditions that you can easily parcel and hand over to you is music, because there are music teachers who have migrated from India to stay here and still teach in a very traditional way.

Because music carries two things. One is just the music, the sound, the other thing is— it’s all about God, prayer, love, all these things. So it teaches values also. When you’re small, we know you need that. And it teaches discipline also. Because there’s a lot of learning, and getting to pronounce, and it helps a lot. So it’s that question of concentration, all these things play into it. So that is why we put you there. It’s a great tradition, and we didn’t want you to miss out on it.

My father knew that learning this music was of the utmost essence. He knew that whether sitting under the window of another child’s house or on a yoga mat covering the cold linoleum floor of Tara Aunty’s basement, music can encourage young minds to grow into free-thinking individuals with a zest for life that only creativity can bestow. He gathered the values that he had spent years discovering on his own musical journey, parceled and handed them to his children to pass on our family’s story of music.

The way the past three generations of my father’s lineage learned music evolved over time. His parents, my grandparents, learned Carnatic music as a “let go” from the rigidity of a life of prayer; Dad discovered the value and beauty of both and used them to recognize the importance of tradition, community, and listening; in turn, he gave my sister and I the chance to carry the torch of our heritage and do justice to their stories. Because of my dad’s values, I can see music the way he does: the pinnacle of humanity, a gift that enables us to discover and explore the world while enjoying every moment of our time in it. These ideas are my father’s musical legacy.

Glossary of terms:

Pooja: A prayer ritual performed by Hindus. Done to express devotion to a deity or deities.

Bhajan: Religious songs often sung at poojas, but also included in religious festivals.

Raaga/ragam: A pattern of notes, arranged similarly to solfege in Western classical music, with particular intervals and embellishments to denote the raaga’s signature. Used as template for improvisations through akaram.

Tabla: Traditional Indian percussion instrument made of two hand drums of different size tied together; different parts of the hand and amounts of pressure are used to modulate pitch.

Nadaswaram: A double-reeded, oboe-like instrument. Often used as the melody instrument in wedding processions and festive celebrations. Produces a tinny, reedy melody that is very loud.

Bhavam: Loosely translated from Sanskrit to English as “emotion” or “intention”; used by Carnatic musicians to describe the energy with which they sing to the Lord.

Mridangam: A sideways barrel-shaped drum; like a tabla, heads are different sizes. Fingers are used for eighth, sixteenth, or thirty-second notes, while the heel of the hand or palm is used for deeper kick notes on the quarter or half beat.

Kacheri: Carnatic music concerts, often made of a vocalist, percussionist, and occasionally a violinist. Can include a number of other instruments.

Akaram: A vocal improvisation by Carnatic vocalists, sung entirely on the vowel “α (ah).” Requirements of a successful akaram are that it maintains the rhythm of the song and signature of the ragam.

Tadh Twam Asi: Loosely translated from Sanskrit to English as “It is You” or “That is You.” One of the grand pronouncements of Vedic scripture. Used to explain that, among other concepts, the divinity within yourself and God is one and the same.

Recent Comments