Incorporating both personal anecdotes and culturally relevant works such as Ban Zhao’s “Lessons for Women,” Grace Huang reflects on the significance of femininity in her life. She skillfully addresses intergenerational differences in perspective regarding what it means to be a woman, inspiring an important discussion about the limitations of the gender binary. Huang also reflects inward, describing her own journey towards self-worth, and ending on a note of mutual understanding and appreciation of different perspectives. –Charlotte Rubel ’22, Editorial Assistant

Femininity between Generations

Grace Huang ’24

My parents were both born in Pingxiang, Jiangxi Province, China. My brother and I were born in Palo Alto, California, United States of America.

Growing up, my mother always pressed a certain type of femininity: Don’t laugh so loudly, and cross your legs. Drink your goji berry soup, it’ll make you pretty. No, you can’t go with your brother to your friend’s house because they’re playing video games, and you’re a girl. Don’t go to an all-women’s college, you won’t be able to meet boys there. That last one, I suppose, could be seen as a classic Asian parent concern. Even the last character of my Chinese name, 佳 jiā, means elegance and beauty (although my mother recently admitted that she had chosen that character because it was phonetically similar to another character, 加 jiā, which is used in the Chinese translation of California, 加州 jiā zhōu).

My mother’s idea of femininity coupled with my own personality—some would call me a tomboy, although I don’t personally like that term because it enforces the gender binary—made it very difficult for us to see eye-to-eye. I began to subconsciously hate the kind of femininity my mother pushed, as I thought she was trying to make me conform to something I didn’t want to be. This conflict intensified as I grew older and became more acquainted with the feminist movement that was being brought back into the public eye with renewed fervor, particularly in the United States. I began to wonder why my mother couldn’t just accept that I was different from her—why she couldn’t just accept that I expressed myself differently than her, that I liked different things than her, that I wanted to live a different life than hers. My affinity for what she thought were things meant for boys didn’t mean I was any less of a girl. Right?

That, at the time, was the heart of our struggle—and my own personal struggle, as well. What my mother tried to impress upon me still weighed heavily. I blamed her and the life she had lived back in China. I turned my eyes away from her and my—our—culture. I was ashamed of everything: of refusing what my mother wanted to do, of putting up the false front my mother pressed onto me, of simply being myself.

Then, I read Ban Zhao’s Lessons for Women.

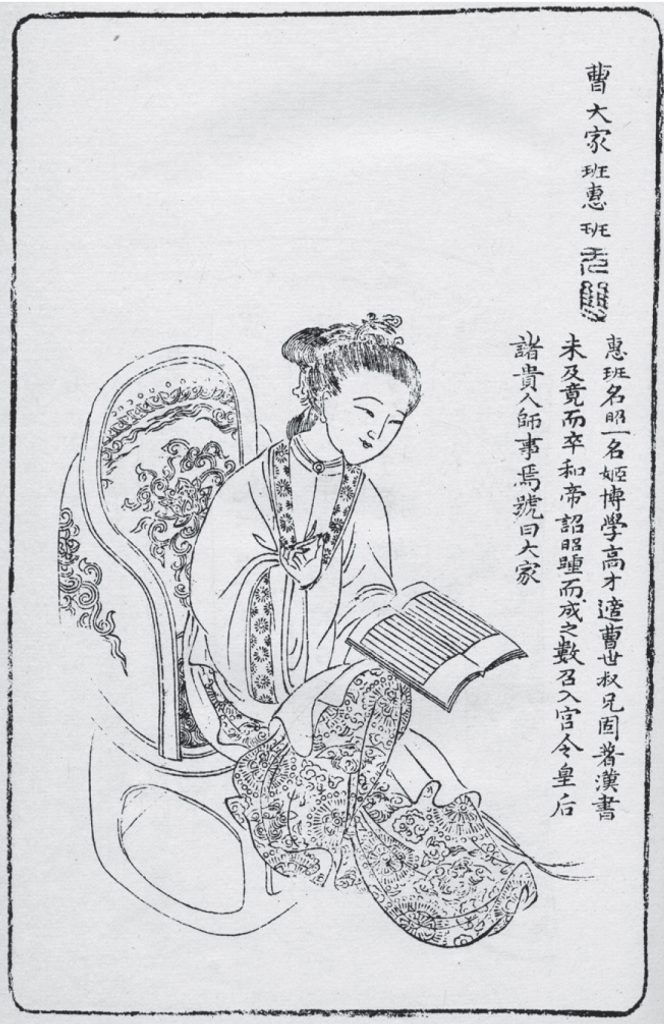

Ban Zhao (45–116 CE) was a famous historian who lived in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) and who wrote one of the most memorable works of ancient China—Lessons for Women. It was so famous that in the late Ming Dynasty (1368 CE–1644 CE), morality books—books instructing people how to act—written for women often featured stories of Ban Zhao teaching her students how to act appropriately.

Nowadays, the book might be considered prescriptive in a… rather contentious manner, some might say. Noteworthy passages include “let a woman modestly yield to others; let her respect others; let her put others first, herself last” and, “as a matter of fact the purpose of these two (the controlling of women by men, and the serving of men by women) is the same”, not to mention, “a woman (ought to) have four qualifications: (1) womanly virtue; (2) womanly words; (3) womanly bearing; and (4) womanly work”.

In essence, Ban Zhao taught young women that they should be compliant and obedient, perfect in all “womanly” aspects of life. It all sounded eerily familiar to me. Ban Zhao’s description of womanly virtue and womanly words especially rang true: womanly virtue is described as guarding chastity and exhibiting modesty, while womanly words means avoiding using vulgar language and wearying others. But, more than that, one sentiment stuck out to me in particular: that only virtuous, beautiful, modest, and respectful women can rely on their sense of duty to make their affection sincere—that women have to be virtuous, beautiful, modest, respectful, and hard-working in order for their affection to be understood and accepted.

Virtuous, beautiful, modest, respectful, and hard-working. I know those values well. Almost too well. They are too reminiscent of what my mother tried to impart onto me—too similar to be a coincidence. Some of Ban Zhao’s teachings are still central to my experience as a woman, almost a thousand years later.

That’s both amazing and terrifying.

Seeing the original work that was the source of the femininity my mother held in such high esteem brought an entirely different perspective into the mix. This new perspective, I doubt that hard-headed and yet terribly insecure high school me ever would have understood. Ban Zhao’s teaching dictated that, unless I had those five values, my affection would never be accepted or believed. There was a reason my mother pushed me to take these ideas as my own and to live by them.

My mother’s motives went far beyond simply trying to control me, as I had thought when I was young. She believed that if I didn’t have these five values, my affection and intentions would never be properly received. Whether she knew about Ban Zhao’s teachings or not, those kinds of morals had surely been instilled in the culture and the belief of how women should act. Despite the movement to push away all aspects of imperial China in the 20th century, the ideals of femininity and how women should act remained alive and well in the morals and values of people. Perhaps, the memories of Ban Zhao’s teachings remained most vividly in people who were not involved in the movement to reset the culture, people who lived rural, disconnected lives. People like my mother. In the end, she had been trying to instill in me values that she thought were best for me.

I know. Sappy, right? If there’s one word that doesn’t (usually) describe me, it’s sappy. But coming-of-ages are almost always sappy in some way, shape, or form.

Looking back on it now, I can’t say that I liked my mother’s attempts to sway my expression of myself and my femininity; I still don’t like them now, even after I’ve come to terms with who I am and how I comfortably express myself. But, as much as this is a story about me discovering myself, this is also a story about my mother and her growth as a parent. She’s come to see that I am my own person with a different life experience and perspective than her, just as I’ve come to see her as more than just an authority figure attempting to control my every action. I don’t resent her for what she did—rather, quite the opposite. I’m grateful for what she did, because I know now that she was truly doing what she thought was best for me.

And as much as I find that I vehemently disagree with and dislike Ban Zhao’s Lessons for Women, I can’t help thanking it for helping me understand what my mother was raised to believe, and for helping me come to terms with a part of me I’ve always felt deeply ashamed of.

Work Cited

Guliang, Jin. “Ban Zhao as depicted in the Wushuang Pu” (無雙譜, preface 1690). “File: Ban Zhao – Wushuang Pu (pref 1690, 1961).jpg.” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 20 Jul 2019, 02:13 UTC. commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Ban_Zhao_-_Wushuang_Pu_(pref_1690,_1961).jpg&oldid=358764548. Accessed 23 August 2021.

Qi, Gai (改琦), 1773–1828. “This depicts the historian Ban Zhao (班昭).” Famous Women (列女圖), 1799. “File: Famous Women, 1799 (L).jpg.” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 25 Sep 2020, 16:41 UTC. commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Famous_Women,_1799_(L).jpg&oldid=471090240>. Accessed 23 August 2021.

Shangguan, Zhou (上官周, b. 1665). “Ban Zhao”. “File: Ban Zhao.jpg.” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 10 Feb 2021, 12:04 UTC. commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Ban_Zhao.jpg&oldid=531840778>. Accessed 23 August 2021.

Zhao, Ban. “Lessons for Women.” Pan Chao: Foremost Woman Scholar of China. Trans. Nancy Lee Swann. Ann Arbor: U of MI Center for Chinese Studies, U of MI Press, 1960: 82–90.

Recent Comments