Responding to the horrors of the COVID-19 pandemic, Jane Brinkley turns to the sublime: the sense of awe we feel when witnessing a force of incredible magnitude or power. Brinkley uses two narratives from the AIDS epidemic to exemplify the sublime — David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America — and through these narratives offers a powerful commentary on life, death, and the art birthed by enormous tragedies. –Ari Jewell ’22, Editorial Assistant

Heaven Is a Place in Your Head: COVID-19, Angels in America, and the Sublime

Jane Brinkley ’24

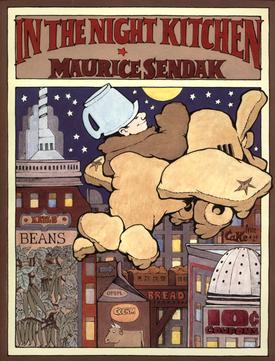

I don’t always feel like reading these days, but who does? The pandemic thwarts any attempt to remain steadily focused on a narrative through-line, and besides, my untouched sci-fi novels feel, at first glance, closer to some terrible, days-near present than the usual “what if” escapism with which a novel has always whisked me away. Reading In the Night Kitchen to my six-year-old cousin is more engaging than the average political think-piece nowadays—I find myself pleasantly submerged in the grandeur of those big, faceless chefs, the tons of dough into which plops the little naked boy plucked from his bed. Beholding comically gigantic bread allows me to consider my own size, my insignificance: maybe in times of terrible illness, there is something comforting about the sublime.

First introduced by John Burke in the 18th century, sublimity refers to the overwhelming feeling of astonishment or rapture that occurs when one beholds something of great magnitude or power from a safe distance—the strongest emotion, he thought, that humans are capable of feeling. The COVID-19 pandemic has provoked a new aesthetic and affective repertoire in many that feels sublime: take, for example, the early fly-by videos of miles and miles of desolate cities, or the ever-mounting online charts meant to represent the shapeless mass of infections and deaths. Scientists and statisticians have tried to render the sheer, overwhelming loss from the illness through comparisons—“imagine that ten concert halls worth of people have died”—but such examples only confuse us; we cannot, after all, literally see the accumulated dead piled up in concert halls, just as we cannot see the virus itself. The sublime thrives on incomprehension, on the invisibility and inscrutability of some massive whole. We stay cooped up in our homes, observing the incomprehensible numbers becoming more incomprehensible, and the little details in life become less important. We stop worrying so much about those things that don’t align with our values; we gain perspective.

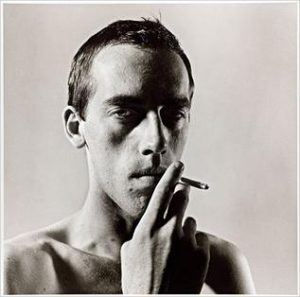

It was in ruminating upon this that I picked up David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives. Wojnarowicz, a gay, unhoused man made famous for his livid, densely symbolic art, wrote the book a year before he would die of AIDS. The memoir is commanding, urgent, and rambling; at times he fills a page or more with the same run-on sentence. Wojnarowicz is profoundly political, but not preachily so—in fact, his words vibrate with a sort of radical honesty that slashes through the vaguely didactic truism I’ve grown used to in much public scholarship about COVID-19. In many ways, he seems to be elegizing something that was not ever granted elegy: the death of a gay man with AIDS, the death of himself, whatever that means. But if, as ACT UP, the activist group to which he belonged, says, SILENCE = DEATH, then Knives is very much alive.

In his first essay, Wojnarowicz, close to death, drives away from a sexual rendezvous with a stranger and squeezes his eyes shut for quarter-mile swaths of highway. He writes, “I feel that I’m caught in the invisible arms of government in a country slowly dying beyond our grasp. There is something singing of this, something in the currents of wind and breeze floating along the black electric cables lining the roads, something I can’t see or touch but moves in the shape of vowels and uttered sounds like spinning soft bodies of birds playing with the sky…. Hell is a place on earth. Heaven is a place in your head” (32).

In Angels In America, this not-so-distant pandemic forces ordinary people to reckon with the sublime. Prior, a gay man dying from AIDS, speaks to his partner Louis about a newly-discovered dimension of his ancestry—a ship captain and oil merchant to whom he is related sent seventy women and children off in a lifeboat as his operation sank to the floor of the Nova Scotia coast. As the weather roughened, Prior explains, “they thought the boat was overcrowded… the crew started lifting people up and hurling them into the sea… people in a boat, waiting, terrified, while implacable, smiling men… seize… with no warning at all” (47–48). Prior’s description hinges on the oblivious violence of nature, and the unjust randomness of death. He is removed from the danger of the unfathomable loss by time, and the object (in this case the mass of dead women and children in his imagination) completely fills his mind. As he goes on, he adds that, “when time is running out, I find myself drawn to anything that’s suspended, that lacks an ending… no judgement, no guilt” (48). He’s rejecting, in essence, the prescriptive approach that organized religion might take in acknowledging the magnitude of loss. Instead of presuming he can comprehend, Prior accepts that he will never do so—and this incomprehension frees him to experience the sublime, to accept a sort of relative smallness that ultimately makes him bigger in more important ways.

In the final monologue of Angels in America, Harper contemplates such a question as she sits on an airplane bound for San Francisco. As she floats into the upper echelons of the atmosphere, she reflects: “I saw something that only I could see … Souls were rising, from the earth far below, souls of the dead, of people who had perished, from famine, from war, from the plague, and they floated up… the souls of these departed joined hands, clasped ankles, and formed a web, a great net of souls… the outer rim absorbed them and was repaired” (275). Harper, who sits at a safe distance from her vision, is made small by this magnitude of death. The little trivialities of her life (she is “sick of details,” (107)) are thrown into harsh relief, and she feels situated in a greater, more awesome whole, which brings about the sublime. Rather than the souls of the AIDS dead being absolved or forgiven, they are repaired. This is a sort of Judgment Day, but a very Earthly one—a situated observation and acknowledgment of incomprehension, rather than an assignment of guilt, is the defining action that Harper carries out.

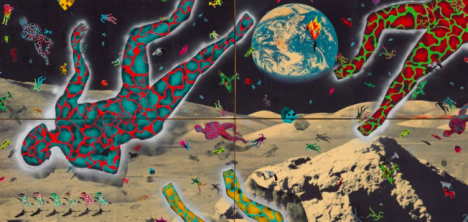

In 2010, 18 years after Wojnarowicz’s death, members of the Catholic League stormed the Smithsonian Museum in D.C. to protest an exhibition of his art. Works such as Science Lesson (1982–83) and The Fire in My Belly (1986–87) were deemed offensive and anti-religious, and parts of the installation were removed. Some of his pieces are inflammatory—The Fire, for example, depicts a cross covered in squirming ants—but others are, to my eye, not. Rather, they are, in many cases, sublime, depicting bodies hurled through outer space, sleeping giants, and reddish skeletons propped up against planets. If heaven is, as Wojnarowicz hypothesizes, a place in our head, then maybe the sublime is a threat to absolutist notions of life and death—a threat, in other words, to the forces that sought to discipline and underplay the HIV/AIDS crisis. Maybe paintings and plays from COVID-19 will look, too, a bit like In The Night Kitchen–earth-shattering, incompressible, and utterly beautiful in their own sublime sort of way.

Works Cited

“David Wojnarowicz.” Artnet. www.artnet.com/artists/david-wojnarowicz/. Accessed 6 Dec. 2020.

Hujar, Peter. David Wojnarowicz. 1981 Photograph. Whitney Museum of American Art. New York.

Kushner, Tony. Angels In America: a Gay Fantasia on National Themes. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1995.

Quinton, Anthony. “Burke on the Sublime and Beautiful.” Philosophy, vol. 36, no. 136, 1961, pp. 71–73. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3748935. Accessed 6 Dec. 2020.

Sendak, Maurice. In the Night Kitchen (Cover image). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_the_Night_Kitchen#/media/File:Sendak-nightkitchen.jpg. Accessed 23 Aug. 2021.

Wojnarowicz, David. Close to the Knives: a Memoir of Disintegration. London: Canongate Books, 2017.

Wojnarowicz, David. Science Lesson.” 1982-83. Original. Gracie Mansion Gallery, New York.

Recent Comments