In analyzing the written and cinematic works of Joan Morgan, Beyoncé Knowles, and Audre Lorde, Gracia Bareti explores how these three women use artistic self expression to challenge the stereotype of the Strong Black Woman. Her rich analysis examines how the Strong Black Woman stereotype has been enforced externally and internally in the lives and minds of Black women. Ultimately, she powerfully illustrates how Black women use their art to freely express themselves, connect with one another, and re-define themselves. –Caty Maloney ‘22, Editorial Assistant

Not Yours: The Solemn Art of the Strong Black Woman

Gracia Bareti ’24

“You do not have to be me in order for us to fight alongside each other. I do not have to be you to recognize that our wars are the same. What we must do is commit ourselves to some future that can include each other and to work toward that future with the particular strengths of our individual identities. And in order to do this, we must allow each other our differences at the same time as we recognize our sameness. “(Audre Lorde, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde, 217)

Black women have taken on all of life’s burdens and they have done it on their own, Audre Lorde tells us, even though life is a partnership–black men and women live through the same oppressions–and no one gender should have to take on all of the burden. This unfairness is captured in the Strong Black Women (SBW) stereotype that ultimately disregards black women’s humanity and damages their mental health. Because they have to be strong, black women cannot show weakness by discussing their trauma and frustration with how society treats them. They have experienced racism intertwined with sexism even from other black people, but they have nonetheless been expected to suppress their emotions for the benefit of the race. They have to take care of everyone but themselves.

Black women use outlets such as music and writing to address their feelings and thoughts not for the benefit of men or the white elitist society we live in, but for themselves, conclusively building a community for black women. Many black people, but especially black men, have developed a deeply rooted self-hatred as a result of systems of oppression, but black men often project these negative emotions onto black women: in response, black women have countered these onslaughts by staying true to themselves through their art, leaving it up to the world to interpret and recognize the harm of the SBW stereotype. The flexibility inherent in aesthetic interpretation makes it a powerful expressive medium for black women to support one another. Writer Joan Morgan, pop artist Beyoncé Knowles, and writer Audre Lorde all use art to express themselves and to connect with other black women. They’re aware that no one will ever understand black women except for black women, as they are the only ones who’ve encountered the stereotypes used to oppress them.

In her book, When Chickenheads Come Home To Roost, Joan Morgan describes the figure of a SBW as someone who conquers all of life’s challenges with ease and provides support for everyone while not expecting anything in return (87). The SBW persona is a double standard, as it forces black women to nurture everyone, but not hold that same expectation for anyone else. Morgan argues that black women should leave this double standard behind. She writes, “What I kicked to the curb was the years of social conditioning that told me it was my destiny to live my life as a BLACKSUPERWOMAN Emeritus,” asserting that black women know that how they’ve been treated is wrong (87). The “kicking to the curb” reference, often used regarding relationships, hints at the frustration black women feel within their relationships with others, especially black men, for not reciprocating the same compassion and care. Morgan addresses the impact these stereotypes have on black women and tries to humanize and personalize the negative effects the SBW stereotype have on black women, who are frustrated with how society constrains them to roles they do not choose. Morgan’s writing expresses this frustration in the effort to fight back, and asserts that the social conditioning dictating how black women are viewed is what needs to be “kicked to the curb.” Through writing about it, she frees herself from the “super blackwoman” stereotype: by naming this stereotype, she opens the conversation about the impact of this damaging trope on black women’s experience.

Similar to Morgan, Beyoncé uses art as a form of liberation and expression through her visual album Lemonade, which, through the use of cinematography in collaboration with symbolism found in nature, gives viewers a closer look into the experience of being a black woman.

ARVE Error: src mismatchprovider: youtube

url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5pM5FD6aT0&t=2s

src in org: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/v5pM5FD6aT0?start=2&feature=oembed

src in mod: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/v5pM5FD6aT0?start=2

src gen org: https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/v5pM5FD6aT0

Beyoncé uses Lemonade as a platform to be vulnerable to the world about her realities. She is first a woman and isn’t exempt from experiences of disappointment and betrayal. She is not a Black Super Woman just because she has built an empire for herself and has maintained a collective persona in the public eye. The intimacy she tries to build with viewers is exemplified through personal family clips from her youth with her father that expose the reality that black girls are forced to grow up too quickly due to cultural stereotypes of black girls as promiscuous and self-sufficient. She invites viewers to witness her at her most vulnerable and to realize that even an icon such as Beyoncé endures pain and suffering.

In the song “Daddy’s Lessons,” Beyoncé tells us the most profound lesson her father taught her: how life would treat her as a black woman. She states the lesson her father taught her: “He said take care of your mother/Watch out for your sister … When trouble comes to town/And men like me come around.”

Here he acknowledges that his actions impact those close to him, such as his wife and daughter, but he still sees it as his daughter’s responsibility to take care of them. Although he’s aware of his mistakes, he isn’t being accountable. Instead, he communicates that his daughter must suffer the repercussions. His doing so provides Beyoncé with a more powerful lesson: her girlhood is deemed of no importance, as the world has already promoted her to a SBW.

Beyoncé wrote this song to give voice to the black girl that still lies within every black woman: she holds black fathers accountable for their actions as parents and for forcing daughters to take on a parental role. In writing this song, Beyoncé provides her father with a lesson that the work that must be done towards disrupting stereotypes isn’t just the work of black women but also that of black men.

Because they are deprived of their girlhoods, black women are conditioned to endure their emotions in silence, behind closed doors. In Lemonade, forms of nature, such as water, are used to symbolize and bring these emotions to life. The beginning of the film shows a scene of Beyoncé drowning by herself, which coincides with water symbolizing fertility, a process that Beyoncé had struggled with while suffering several miscarriages. In the brief interviews that discuss her losses, however, the media skirt away from her innermost feelings, failing to recognize that black women have deep interior thoughts and emotions: these women are forced to be composed SBWs, to be available to everyone else (including their fans), and never giving themselves the freedom to grieve. Beyoncé could have asked one of her countless supporting performers to act in the underwater scene in Lemonade, but still, she wanted to do so herself to show that she’s experienced pain too, through the miscarriages she has endured and the disappointment she has suffered from the black men in her life. The media may miss the important and moving reality of Beyoncé’s deep inner turmoil, but like Joan Morgan, she insists on using her artistic platform to express it anyway.

The message about loneliness and isolation that Beyoncé shares in Lemonade connects to Morgan’s claim about the black woman’s psyche. Morgan states, “I’d internalized the SBW philosophy: No matter how bad shit gets, handle it alone, quietly, and with dignity. The truth was, much of what was going on in my life shouldn’t have been handled silently or stoically by anybody” (90). Morgan’s statement asserts that black women are aware of the trauma they’re going through, but, similar to Beyoncé’s message of drowning, black women feel alone. Water also symbolizes life, and since the video concludes with Beyoncé drowning once again, it shows how black women may be going about their days as if everything is okay, but meanwhile they’re drowning within themselves due to the hurt that they never asked to endure, especially alone. The power of these drowning scenes allows for black women to see themselves through Beyoncé and to feel seen—to feel that someone of such stature can relate to their experience and notices them, alleviating some of that loneliness.

Stereotypes have the power to subjugate black women to be strong for others, specifically black men, a power that stems from the self-hatred that black men struggle with due to being victims of abysmal systems of oppression. Black men take their frustration out on black women, because they’re the only other community that has encountered the same racial discrimination yet still tolerates their behavior out of love for them and out of a feeling of racial solidarity. Audre Lorde discusses the aggressive behavior of black men in her book Sister Outsider: “The true focus of revolutionary change is never merely the oppressive situations which we seek to escape, but that piece of the oppressor which is planted deep within each of us, and which knows only the oppressors’ tactics, the oppressors’ relationships” (187). For Lorde, the real solution is to recognize the oppressive behaviors that are within all of us, that we’ve learned from our oppressors. Although black men’s actions come from a place of pain, that pain doesn’t justify the way they have consistently mistreated black women.

Beyoncé shares the impact of the mistreatment black women experience through the symbolism of a cup. In a scene from Lemonade, she features a close up of a cup with a visible crack in the middle of it. The cup is damaged, but is still in working condition: it exists, still, to provide a vessel for other people to drink from. The cup is similar to a black woman; although they go about life faking their very language, the pain of being available to everyone but themselves stays like the crack in the cup. This scene causes viewers to recognize the cracks black women live with and how they are not as easily visible because they have to maintain the image of SBW. A cup’s objective is for people to place liquids within it and drink, relating to the film’s lemonade theme—a beverage meant to nourish others. A cup and lemonade provide nourishment, but when they aren’t taken care of properly, over time, a cup will crack, which resonates with the SBW stereotype. If society continues to beat away at black women by disregarding their feelings and existence, they will break.

Although stereotypes have been the root of most of the suffering of black women’s experiences, black women continue to fight back through the unity they find within art. Black women can use art to share their similar, painful experiences, which gives art a therapeutic power that unites black women. When Beyoncé sings, “Okay ladies, now let’s get in formation,” this is a call to action for black women to support one another because no one understands their experience better than each other. Black women share their art with the rest of society, not to gain others’ validation, but to emphasize that black women are their own people and don’t owe anyone anything. In Lemonade, when Beyoncé states, “the audience applauded but we can’t hear them”; she’s saying that black women don’t want society’s pitying applause for how “strong” they are, because they have received that all of their lives. Pity will not change the pressure that is placed on them to be everyone’s rock. Instead, it’s what the audience does after hearing and observing black women’s artistic creations that will make a difference in improving how black women experience life.

Works Cited

Harris, Kristopher. “Beyoncé performing during The Formation World Tour in Raleigh, North Carolina on May 3, 2016.” Photograph. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beyonce_performing_in_The_formation_tour.jpg. Accessed 28 August 2021.

Lorde, Audre. The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde, reprint. New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Morgan, Joan. When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-hop Feminist Breaks it Down. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2017.

Beyoncé. Lemonade. Parkwood Entertainment, 2016. www.beyonce.com/album/lemonade-visual-album/. Accessed 20 October 2020.

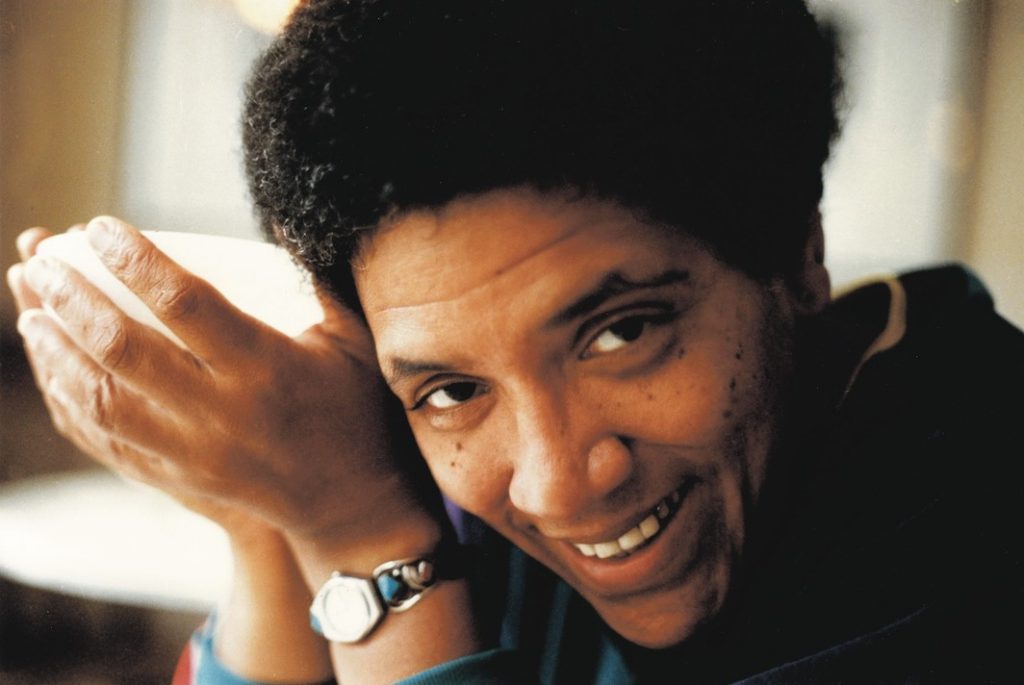

Schultz, Dagmar. Audre Lorde, Berlin, 1984. Photograph. Cover photo for Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992. Documentary, dir. Dagmar Schultz, 2012.

Recent Comments