Drawing on her experiences of living in the South and the mysteries within her family’s history, Georgia Coats passionately investigates the origins of the collective white memories of the Civil War. By questioning the ways in which history is passed down and altered over time, she deftly assesses the reasons why certain histories are preserved, erased, or fabricated to serve different ends. Through her personal experience, Coats demonstrates the importance of truth-telling and historical contextualization in the pursuit of a more honest and accountable America. –Caty Maloney ‘22, Editorial Assistant

Rediscovering the Civil War: How We Are Building Truth from Its Myths

Georgia Coats ’24

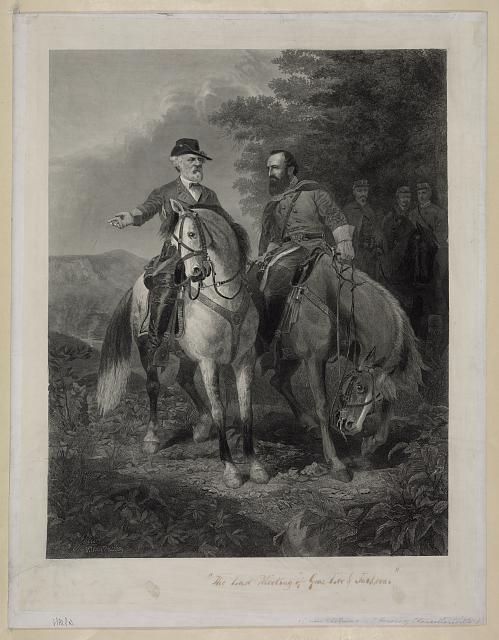

Deep in my earliest memories is a distinct image of a magnet that was once placed on my home refrigerator. It was a copy of The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson—and it was my favorite of all the other magnets, because I loved the vivid red and chestnut colors of Stonewall Jackson’s horse, Little Sorrel.

Though I was still too young to understand the Civil War as a concept, I already felt the pull of nostalgia towards these Confederate figures. But the narrative that gave me this nostalgia was false, concocted by followers of the Lost Cause—a conglomeration of falsehoods that insist the Confederacy was a noble country which was simply outgunned by the Union in 1865. As a result of Lost Cause, the memory of the white South has become selective regarding the Civil War, over time losing sight of the nuances of history in favor of parroting an untrue narrative. As monuments fall, history is reassessed, and myths brought to light, the war has become a battleground of legacy and memory. Which legacies are true, and which ones are based in fabrication? Has our collective memory been shaped towards myth, or the facts of reality? These difficult questions are what we must ask if we are to finally leave the Lost Cause behind.

A unique experience of living in the American South is how much the Civil War intrudes upon everyday life. Louisville, Kentucky especially is an odd background for my own experiences with the war. Kentucky was a border state, locked in a struggle between the Union and Confederacy. Our state capitol went back and forth between the two sides, a reflection of the fact that President Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, both hailed from central Kentucky. It seems as if Kentucky was destined to be forever torn in two, a state that stayed with the Union but contained a populace filled with Confederate hearts. A common, wry saying is that Kentucky joined the Confederacy after the Civil War, and I believe this is true. Many of the local monuments to Confederate icons were erected long after the war, during that period of nativism, isolationist theory, and nostalgia found between 1900 and 1940. A statue of Jefferson Davis, erected in 1936, stood in our state capitol in Frankfort, a plaque proclaiming his patriotism and heroic nature accompanying his grand pose. He faced off against Abe Lincoln in the capitol rotunda for nearly a century before his loss of the war was finally accepted. He left in defeat during the summer of 2020, sent away by Kentucky’s governor and historical commission. Though I have little memory of the trip I made to the state capitol with my fifth-grade class, I doubtlessly saw this statue and heard an explanation of Jefferson Davis’ presence in the capitol. Like everyone else, I swallowed what little platitudes were offered about memorializing a traitorous man who fought tooth and nail to keep humans in bondage.

While contemplating my earliest thoughts on the war, I recollected a tale my mother enjoyed telling me as I got older. In 1969, my third-great uncle Everett Pitman on my mother’s side passed away in Dallas County, Missouri. According to family legend, great treasures were hidden in his attic, and rumor claimed it contained relics of our own Civil War hero, who honorably lost his life in battle. The hero would have been Everett’s uncle, having come with his brother and mother from North Carolina. Oddly enough, it had always been assumed our ancestor was a Union soldier. When my grandmother’s great-aunts, Alice and Laura, came to clean out the attic, they found an old trunk full of the promise of Civil War heroes.

They excitedly opened it, avidly awaiting the familial relic. A pristine, folded gray uniform met their eyes, with a bullet hole in the chest. I first heard this story from my mother, who recounted it a few times over the years and always ended the story claiming the uniform was anonymously donated for posterity. When I decided to write about the uniform, I called my grandmother to make sure I recorded the details correctly. I was told that the uniform was not anonymously donated. In fact, it had been given to the Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, located in central Missouri, in commemoration of its opening in 1966. A dinner was even given by the battlefield to honor the donation (Light).

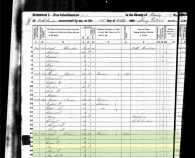

Some aspects of the story made little sense to me at first. Why was the soldier assumed to be Union during the 1960s, a hey-day of Confederate nostalgia? Clearly, there was some shame in the family relating to the Confederacy, but when or why was a mystery. I discovered while looking at old census records that there were three Pitman sons, rather than two as I had always been told. Why had one been entirely forgotten? The only record showing that he, Jeremiah Pitman, ever existed is in the 1850 North Carolina census, though he was born in 1836 (U.S. Census 1850). He is mysteriously absent from the family’s 1860 census in Arkansas (U.S. Census 1860). Perhaps he died, but two Jeremiah Pitmans enlisted in the Confederate army in Tennessee—a state the family would have travelled through to reach Arkansas from North Carolina. This may be more wishful thinking, but I can imagine a family argument over politics and ideology, resulting in a split-off near Nashville.

Then a few years later, a gray uniform reaches the family, announcing their estranged son’s death. Perhaps Jeremiah was forgotten because his family, in the years after the war, felt ashamed of their son’s involvement on the losing side. The youngest brother, William (my fourth-great grandfather), would have hardly remembered his oldest brother, being born in 1856. He might have been told fictitious stories by his widowed mother in the 1870s, which grew and grew until that chest contained not a traitorous Rebel, but a heroic Yankee.

I found this story an incredible parallel with the selective memory of the white South, although my family went in the opposite direction. The idea of William’s widowed mother being the guardian of her family history brought to my mind the many Southern women diarists of the Civil War era. One of the most well-known Southern diarists is Sarah Morgan, a woman from Louisiana who was only nineteen when war broke out in 1861. Like other women diarists in the same period and region, Sarah Morgan expresses a lot of hatred, grief, and anger within her private writings. She writes: “‘A Dead Confederacy.’ Fools! The flames are smoldering! They will burst out presently and consume you!” (Dawson 517). I asked my father what he thought of her writings, and he described Sarah Morgan as a “charcoal fire”—a flame which smolders harmlessly on the outside, but burns more violently than any other in the center. Thousands of Southern women like Sarah Morgan became charcoal fires during and after the war. Many of these women coalesced to form the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the guardians of the Lost Cause. The Daughters of the Confederacy are the scorching flame that has set Civil War historiography alight for the last century, driving many families and communities to eliminate what is deemed “unkind and unfair to the South” (McPherson 160). James McPherson, a well-regarded Civil War historian, writes in “Long-Legged Yankee Lies,” a history of Southern censorship in school textbooks, “the [United Confederate Veterans] was a powerful lobby in Southern politics and the [United Daughters of the Confederacy] enjoyed great prestige in Southern communities…the crusade to purge Yankee lies from the schools achieved great success…no book or author was either too important and powerful or too marginal and obscure to escape the censure of UCV and UDC watchdogs” (127). The charcoal fire of the United Daughters of the Confederacy has slowly eviscerated the memories of the Union and former enslaved people, leaving many white Americans with a nostalgic pull towards Confederate figures.

Recently, this generations-long narrative has shifted. As a result of the Charleston massacre, the Charlottesville Ku Klux Klan rally, and the Black Lives Matter movement, the nation has finally begun to take a hard look at itself regarding Lost Cause indoctrination. It is a true period of historic upheaval, with the toppling of monuments, the lowering of flags, and even the removal of the “stars and bars” from Mississippi’s state colors. We are now looking towards a future (no matter how far-flung still) where the Lost Cause will be finally left behind. Now instead of a battle to keep white southern propaganda in power, the Civil War has become the battleground for truth among the history once purged to preserve the “dignity” of Southern soldiers—never mind the dignity of the millions of people treated as chattel for four hundred years.

But in this upheaval, it isn’t just Civil War history that’s being reconsidered. Along with monuments of long-dead Confederates, the United States is full of physical markers of segregation—a direct consequence of the botched Reconstruction era, where freedpeople’s rights were taken away by white “redeemers.” Richard Frishman writes in an article about his series of photographs of these physical reminders, or what he calls “ghosts” of segregation: “Does such erasure remedy the inequalities and relieve the suffering caused by systemic racism? Or does it facilitate denial and obfuscation?” In this passage, Frishman is referring specifically to the demolition of segregation-era signs, such as one advertising “All White Help” at a restaurant in Oregon. This question not only relates to the physical remnants of the segregation era, but the ideological remnants of the Lost Cause, because one really could not exist without the other. The whole nation is finally beginning to understand the lies of the Lost Cause and the white South. But is destroying the remnants of the narrative, like how segregation-era signs are being demolished, just another way of hiding the dark side of our nation’s history? It is clear we have to eliminate this misleading narrative of glorification—but it is still important to make clear its effects for the sake of memory. If we forget, just as my family forgot the truth of our ancestor, we lose sight of our mistakes, and the cycle repeats. We must continue to fight for the truth of Civil War history, but we also can’t simply disregard the false narratives in our battle.

One more casualty of the Lost Cause is Ulysses S. Grant, whose legacy has been erased. Known as the great general who preserved the Union, his 1885 funeral procession was attended by more than a million people. He was laid to rest just off Riverside Drive in Manhattan, in North America’s largest mausoleum. Though grand, it is perhaps the loneliest spot in the city—treated as if burned to the ground by Sarah Morgan’s flames back in 1863. While New York City bustles all around him, he lays forgotten in a quiet corner near the river, hidden in plain sight. Appomattox Courthouse (the place where Lee surrendered to Grant in 1865, located in rural Virginia) received over 6 million visitors in the last 20 years, while Grant’s Tomb welcomed fewer than 800 thousand (U.S. Department of the Interior). Robert E. Lee is laid to rest in a small chapel at his beloved university Washington and Lee, greeted by tourists and students every day. No such love is found for Grant. Sarah Morgan’s warning speaks to me when I think of Grant’s tomb, her anger ironically penned just after the fall of Vicksburg. Frederick Douglass once reprimanded a New York audience 168 years ago on the Fourth of July: “your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery… your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are… mere… hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages” (608). Although Douglass gave this speech eight years before the war, it rings true with the endless censorship of textbooks, and the erection of thousands of Confederate monuments. We cannot let Sarah Morgan’s charcoal fire continue to eviscerate the history of the Civil War and beyond, because the grief and anger she felt, and many people today still feel on behalf of the Lost Cause, are incredibly powerful weapons that can destroy anything put in their pathway. The war is still being fought today on the grounds of truth and reality versus lies and myth, whether the discussion is about systemic racism or the effectiveness of President Ulysses S. Grant, with both attacked with incredible fierceness and bombarded with lies. Our responsibility is to meet these onslaughts with history, truth, and judicious plans for the future, rising above the people who are still burning in 2021 from Sherman’s flames sparked in 1865.

Works Cited

Dawson, Sarah Morgan, and Charles East. Sarah Morgan: the Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

Douglass, Frederick. “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? .” American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation. Ed. James G. Basker. New York, NY: The Library of America, 2012.

Frishman, Richard. “Hidden in Plain Sight: The Ghosts of Segregation.” The New York Times. 30 Nov. 2020. www.nytimes.com/2020/11/30/travel/ghosts-of-segregation.html?action=click.

Julio, Everett B.D. “The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson.” [Original painting] 1869. American Civil War Museum, Richmond. Oil on canvas; [Digital Image of Print] Library of Congress Civil War Online, Library of Congress, 0AD, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004666431/.

Light, Farron. “Interviews with Farron Light (My Grandmother) about the Pitman Confederate Uniform.” Telephone interviews by Georgia Coats. 5 Dec. 2020 and 12 Dec. 2020.

McPherson, James. The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture, by Alice Fahs and Joan Waugh, University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Oldham, Scott. “Grant’s Tomb.” Flickr, 22 Sept. 2009, distribution allowed by Creative Commons License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Census of the United States, 1850; Census Place: Yancey, North Carolina.” National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls: Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C. Year. Roll: 649; Page: 448b.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Census of the United States, 1860; population schedule; Census Place: Jefferson, Carroll, Arkansas.” National Archives and Records Administration microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. Family History Library Film: 803038, p711.

U.S. Department of the Interior. “Stats Report Viewer.” National Parks Service,. irma.nps.gov/STATS/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20R ecreation%20Visitation%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=APCO.

Recent Comments