Introduction:

The Image and the Locomotive

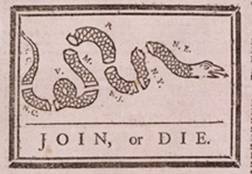

American political cartooning began well before there was a United States of America. Think for example of Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 “Join or Die,” as well as the far more aggressive “Don’t Tread on Me” image of a coiled rattlesnake. That these images continue to stir and speak to us some 250 years after they were drawn is testimony to their importance. Yet despite the importance of railroads in American life in the century or so after 1850, and despite the immense railroad literature produced by historians and enthusiasts, the vast outpouring of political cartoons depicting railroads during these years has largely been overlooked. (1)

![]()

![]()

Library of Congress LC-USZC4-5315![]() http://www.gadsden.info/clipart.html/

http://www.gadsden.info/clipart.html/

The images in this site chronicle the evolution of Americans’ relationship to their railroads; they broadly divide into two categories: those about railroads and those that use railroads as a metaphor. (Of course many images of railroads contain metaphor as well.)

Railroads as Metaphor

Railroads quickly became part of the metaphors and images of American life. They entered American literature, inspiring stories from Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville and many others, and they generated thousands of lines of poetry. Consider the following bit of whimsy from 1840.(2)

Though a railroad, learned Rector

Passes near your parish spire

Think nor Sir your Sunday Lecture

E’ere will, o’erwhelmed, expire.Put not then your work in weepers

Solid work my road inspires

Preach what’ere you will—my sleepers

Never will awaken yours.(3)

As these lines suggest, railroads became part of the language. Cartoonists picked this up a well. A favorite drawing of the 1850s punned on the “train” that followed women’s dresses of that era.

Fair Creature: The Train Is Very Much Behind Isn't It Dear?"

[Harper's Bazar, December 12, 1868

The term iron horse dates from at least the 1850s. We still speak of being asleep at the switch and say someone or something became sidetracked or is on the wrong track.

And so on. Cartoonists also employed these same images, often to depict political campaigns. Many of these say little about the railroad itself, except to suggest its ubiquity in American life. Many others however typically portray it in a positive light, as a symbol of power or inevitability.(4)

Images of the Railroad

Cartoons about railroads in turn fall mostly into three categories – railroads as social institutions, as technology, and as businesses. In addition, there were cartoons BY railroads and their workers in employee and labor journals and in railroad advertisements that constitute a largely separate category.(5)

Social Institutions

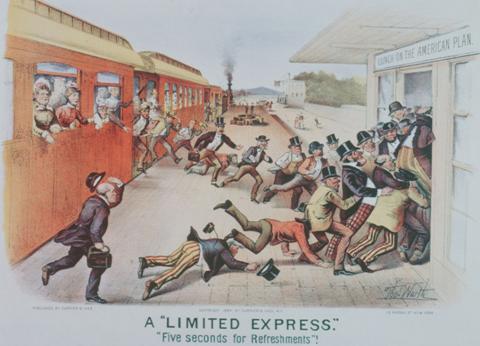

The many thousands of drawings of railroads as social institutions suggest their importance in shaping the everyday lives of men and women. There are endless sketches of the travails of travel, of missing trains, eating bad food, being packed in like sardines, losing luggage or having it destroyed.

[Library of Congress: LC-USZC2-2760]

While Black travelers rarely appeared, and Jim Crow institutions were largely ignored except by Black papers, women travelers were endlessly fascinating as they pressed the bounds of then acceptable convention. These social drawings do more than simply poke fun at us; they help to create and define what constitutes “us.” Losing baggage or having it smashed in train travel or being packed in next to a fat person was one of the definitions of what it meant to be middle class. If you could say “yup, that’s me,” to such drawings you were a member of the club.(6)

Technology

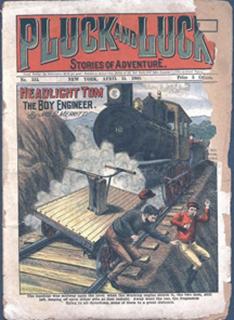

Cartoons about railroads that emphasized technology were less common, but were almost invariably cast in the heroic mold. The locomotive was conquering the prairies, binding the union, or steaming through snow drifts. Many penny dreadful's and dime novels emphasized technology -- the power and danger of trains, for the hero to display the manly virtues of courage, tenacity, integrity, decency. Interestingly enough, women too sometimes played these heroic parts.

![]()

[www-sul.stanford.edu/depts/dp/pennies/home.html;![]() Illus.Police News, Sept. 21, 1895]

Illus.Police News, Sept. 21, 1895]

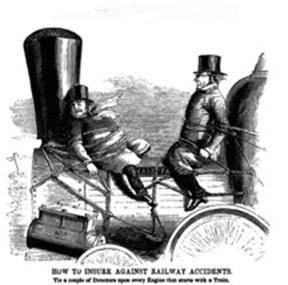

Business Enterprises

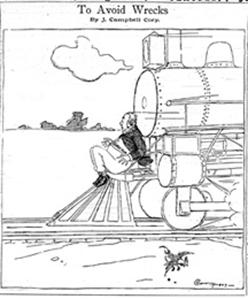

Cartoons depicting the railroads as business enterprises were almost uniformly negative down to about 1910. In the 1850s a spate of train accidents led cartoonists into black humor, suggesting that accidents were part of the excitement of a new technology. But they also began to claim that if directors rode on the locomotive, trains would be much safer. Fifty years later the humor was gone but the biting images implying that wrecks reflected company indifference to safety were still appearing.

![]()

Harper's Monthly, July 1853 ![]() New York World, January 2, 1907

New York World, January 2, 1907

For a discussion of accidents and safety see my Death Rode the Rails (Johns Hopkins, 2006)

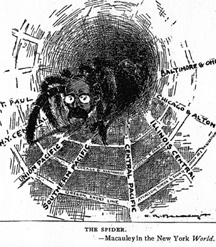

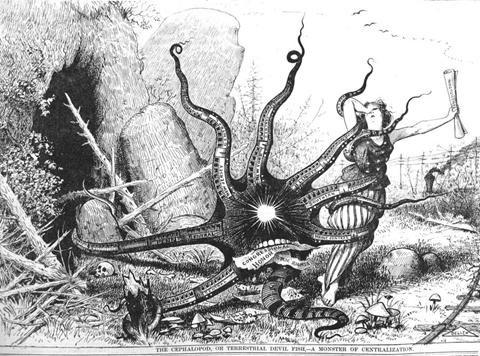

Similarly, individual railroad leaders were usually painted in the darkest hues. Jay Gould cartoons run into the hundreds and they typically depicted him as a financial Mephistopheles, while E. H. Harriman was often portrayed as a monopolist and Wall Street operator, although some images simply depict him as a titan.(7)

![]()

Jay Gould ![]() Edward H. Harriman

Edward H. Harriman

[Frank Leslie's Weekly, July 9, 1887 ![]() Literary Digest, January 1907]

Literary Digest, January 1907]

The railroad itself was Frankenstein’s Monster was or it was The Octopus. It was not the machine in the garden that worried Americans of this era; it was the business and the businessman in the garden.

[New York Daily Graphic, March 4, 1873

Quit and Go Home

The one area where the railroads as businesses received sympathetic coverage from cartoonists’ pens in the years before 1910 was in labor relations. Middle class cartoonists were even more worried by labor revolts – which they usually took to be the results of anarchists and communists -- than they were by the railroads. But even here the carriers were not blameless, for many drawings blamed anarchy on monopoly. It was the carriers’ own sins that led to labor revolts.

Ideas have consequences, and the cartoons presented here are therefore important historical documents. The blistering hostility to the carriers that they reflect and to which they contributed resulted in a wave of state and federal regulatory legislation after 1900. The long term consequences of the new regulatory regime may well have been worse than the railroad “monopolies” ever were, for after 1910 when ICC refused the railroads’ request for a rate increase, railroad profits failed to keep up with inflation. Regulation thus retarded investment and it stifled managerial initiative and technological change.

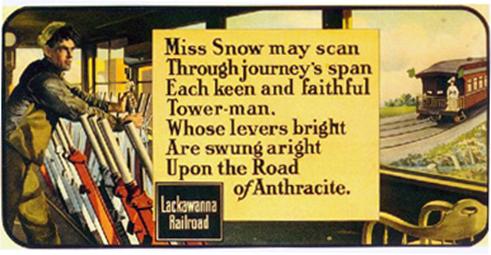

Stung by the public assault and fearful of ever more stringent legislation, the carriers began a massive publicity campaign for higher freight rates and started to advertise their safety record.(8)

[Phoebe Snow Advertisement: ca. 1903-1910

Author's Collection]

By about 1914 the railroads’ changed circumstances began to be reflected in the cartoons of the day, as images increasingly depicted them begging the ICC for pennies and battered by regulation. But if cartoons had helped put public pressure on the legislature and executive to regulate the carriers, they were much less effective in influencing the ICC, which was intended to be exempt from public pressures – a fact that may help explain the agency’s increasingly negative portrayal.

![]()

[Literary Digest, April 11, 1914 and April 18, 1914]

Images By Railroads and Unions

A final category of cartoons about railroads includes those that appeared in company or union publications. Insurance companies sometimes used railroad accidents in their publicity while they occasionally figured in other advertisements as well, often simply as metaphor. Railroads occasionally used humor and caricature in their advertisements and in-house publications and by the 1920s the railroad brotherhoods’ journals also began to use cartooning on a large scale.

The B&O Stressed Efficiency

[B&O Magazine, September 1925

(1) There are many books on political cartooning. I have benefited from Roger Fischer, Them Damned Pictures (Archon books, 1996), Charles Press The Political Cartoon (Associated University Presses, 1981), Paul Somers, Editorial Cartooning and Caricature: a Reference Guide (Greenwood,1998), Stephen Hess, Drawn & Quartered : the History of American Political Cartoons Elliott & Clark, 1996). Stephen Hess, The Ungentlemanly Art: a History of American Political cartoons (Macmillan, 1968). Richard West, Satire on Stone: the Political Cartoons of Joseph Keppler (University of Illinois, 1988).

(2)A nice listing and discussion of works about transportation in American literature is at http://english.cla.umn.edu/faculty/ross/Transport/title_page.htm )

(3) James Smith, “The Railroad Engineer,” The New - Yorker 8 (Mar 7, 1840): 390.

(5) For a discussion of such categories and their essential fuzziness see Press, The Political Cartoon, ch. 1.

(7) Modern assessments of both Gould and Harriman are more sympathetic. See Maury Klein, The Life and Legend of Jay Gould (Johns Hopkins, 1986) and his The Life and Legend of E.H. Harriman (University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

(8) For the ICC see Ari Hoogenboom, A History of the ICC (Norton, 1976), and Albro Martin, Enterprise Denied (Columbia, 1971). The carriers’ publicity campaign has been largely ignored. For a discussion off attempts to publicize safety see my “Public Relations and Technology: The “Standard Railroad of the World”

and the Crisis in Railroad Safety, 1897-1916,” Pennsylvania History 74 (Winter, 2007): 74-104.